|

Stephen M. Sachs University of Indiana/ Purdue University

Indianapolis

.

Remembering the Circle: American Indian Society Before Columbus

Before the coming of Columbus and European colonization, American Indian

tribes were sovereign nations. The more than 500 nations that lived in what

is now the United States were each unique in their political, social and

economic organization, and in their cultures, but they shared many common

values,1 ways of seeing and approaches to living. This provided the basis

for good lives in well functioning societies.

The tribal and band societies of what is now the United States were extremely

harmonious and democratic,providing mutually supportive relationships and

a high quality of life for virtually all of their members.2 Decision making,

while carried out in different ways in different societies, was by consensus,

with everyone effected by a decision having a say in it.3 Political leaders

were facilitators and announcers of decisions, rather than decision makers.4

As those chosen as leaders were people of fine character and ability, they

usually exercised influence in helping the community come to a consensus,

but they had no effective power to command anyone to do anything without

the support of the community. Military leaders could command during a war

party, but warriors, usually, werefree to choose which leaders to follow.

Moreover, military leaders, often, were separate from and subordinate to

civil leaders.5

This was the general pattern both for small and large traditional North American

Societies. The Chiricahua Apaches of the Southwest, for example, lived in

small bands, each with its own consensus based governance.6 They lived by

hunting, gathering, raiding and agriculture. Each band, and within it, each

local group, was guided by one or more recognized leaders assisted by a number

of subordinates. Important decisions were made at band or local group meetings

at which all adults were present and male heads of households usually spoke

to represent their families, though wives and unmarried sons and daughters

might contribute to the discussion. A man would become a leader if enough

people respected him sufficiently to give him their loyalty, and he would

maintain that leadership role only so long as he maintained that respect

and loyalty. People dissatisfied with a local or band leader could simply

move away to another band or group, which worked to make band leaders

sensitive to their members needs and concerns. As in many bands and tribes,

being of good family was an advantage in gaining the respect necessary to

become a leader, and a leader was almost always the head of an extended family.

But the primary basis of leadership was being respected for ability and good

qualities, as demonstrated by his achievements. He must be wise, respectful

of others, able in war, capable in managing his own and his family's affairs,

and generous. Thus wealth was an aspect of qualification for leadership:

as a sign of ability and as a source of the generosity that leaders were

expected to exhibit, in hosting prominent people, putting on feasts, and

in providing for those less well off.

The functions of a Chiricahua leader included being an advisor in community

affairs, a peacemaker, and a leader in war. While leaders could command in

combat, they had no power of control in civil governance beyond what was

supported by public opinion. To the extent that they were respected and were

persuasive (a quality contributing to respect), leaders exercised influence

in the forming of community views. Even as peacemakers, when deviant acts

or major disputes occurred, they only had the authority of mediators. Since

the Chiricahuas needed each other's help in a variety of economic and social

activities (as is normally the case in band and tribal societies), the main

pressure for following social norms, including reaching settlement in a trouble

case, was the pressure of public opinion (in which women played an important

role). Thus leaders were under continuing scrutiny to act well and needed

to be concerned for the needs and views of the members of the community.

In particular, the band leader needed to listen carefully and take into account

the advice of the local group leaders. They, in turn, had to be especially

responsive to leading heads of families, who were obligated to be responsive

to the adult member s of their families. Family relations were wide spread

and quite extended, involving mutual obligations and mutual support amongst

people who economically and socially needed each other to live well.7 Thus

power and influence were widely disbursed in Chiricahua society. Respected

elders had the most political influence, but this influence and respect itself

rested upon the opinions of the community members at large in a culture which

emphasized respect for all community members (and indeed all beings). s of their families. Family relations were wide spread

and quite extended, involving mutual obligations and mutual support amongst

people who economically and socially needed each other to live well.7 Thus

power and influence were widely disbursed in Chiricahua society. Respected

elders had the most political influence, but this influence and respect itself

rested upon the opinions of the community members at large in a culture which

emphasized respect for all community members (and indeed all beings).

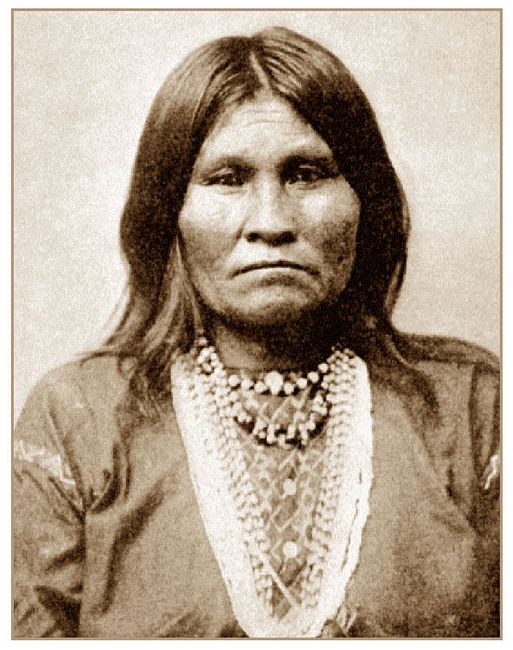

Fig.1: Tshai-Kloge, a Chiricahua Apache woman, from a photo taken in about 1900 (Bureau of American Ethnology [BAE] vol.30, 1907).

The same basic values and underlying pattern of consensus based decision

making were also found in the larger and more complicated tribal societies

in traditional North America, who had not yet begun to develop the attributes

of states. The Dine, generally known as the Navajo, for example, were a society

governed largely at the band level with somewhat more complexity in their

social organization owing to their strong clan structure.8 It appears that

clans (extended family units) were important in public affairs because they

were responsible for the behavior of their own members (e.g., debts,

torts and crimes). Since clans gave considerable emotional and economic support

to their members, pressure from kinsmen, especially elders, was likely to

have exerted a strong influence. In speaking of more contemporary local

governance, Kluckhohn and Leighton describe what oral history says was true

of the old band government and which was typical of traditional Native American

government in general.9

Headmen have no powers of coercion, save possibly that some people fear them

as potential witches, but they have responsibilities. They are often expected,

for example, to look after the interests of the needy who are without close

relatives or whose relatives neglect them [a rare occurrence in traditional

times], but all they can do with the neglectful ones is talk to them. No

program put forward by a headman is practicable unless it wins public endorsement

or has the tacit backing of a high proportion of the influential men and

women of the area.

The two authors go on to say that at meetings, "the Navaho pattern was for

discussion to be continued until unanimity was reached, or at least until

those in opposition felt it was useless or impolitic to express disagreement."10

They point out, however, that while public meetings provided an occasion

for free voicing of sentiments and thrashing out of disagreements, the most

important part of traditional Dine political decision making took place

informally in negotiations among clan and other leaders representing their

respective groups, who regularly discussed community concerns face to face.

An important aspect of the inclusiveness of traditional North American societies

was a balance between women and men in community affairs. in differing ways

in each society, men and women in Native American cultures carried out their

separate functions and had a greater say in differing areas of social life.

But this division of labor did not produce the difference in status and value

that accompanied the dichotomy of social roles in Western society.11 To the

extent that in Western societies it could be said that a man's home is his

castle, among traditional Native Americans one might say that a man's home

was her castle. Among the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), for example, only men

served as chiefs (sachems) on the intertribal council, but women held

considerable power. In certain clans, the women, speaking through the Clan

Mother, nominated the chiefs and had the power to remove them for misconduct.12

In some tribes women served as chiefs, but regardless of their formal role,

women in traditional Native American societies were predominate in their

own affairs and held great influence in public affairs.13 Indeed, a study

of 13 North American societies and multiple society culture areas, north

of what is now Mexico, found that, traditionally, in all but one case, there

was a balanced reciprocity between men and women.14 Further research indicates

that even that one case involved balanced reciprocity.15

Of particular importance in traditional Native American societies is the

collective voice of women, especially of elders, because of the emphasis

on honor and shame in those cultures. Even with all the changes in American

Indian ways that have occurred with the arrival of Europeans and others,

the collective voice of women remains strong to this day. This is illustrated

by an experience of this author one evening at the Sun Dance of the Southern

Utes, in Southwest Colorado. In that sacred ceremony the men at the drum

start the song, but the women around them join in and "have the last word."

That night, after a visiting group of singers finished their turn, no regulars

were available, so a few part-time singers and apprentices, as was I, filled

in under the direction of a young man who just that afternoon had been taught

how to lead by the elder singers. While for the most part the young man's

fine spirit made up for our technical weakness, on one occasion we lost the

song and were ready to let it go and move on to the next. But the women singers

would not allow our indiscretion. They picked up the song and gave it back

to us. And when that song was properly completed, they let us know quite

clearly how we were expected to do our job correctly in that sacred space.

The relative traditional balance of men and women,16 each dominant in their

own spheres, can also be seen today at Southern Ute in the continuance of

the ancient Bear Dance each spring. When, in the Dance, the two facing lines

of men and of women break into couples (or trios), the partners are side

by side with the men facing East and the Women facing West. As the couple

makes the long prance East, the man guides the couple. And when the couple

moves toward the West, the woman guides.

The inclusive participatory democracy of American Indian societies had a

very important impact on the Europeans and their North American descendants

who later attempted to repress and eradicate Native American culture. There

is now excellent evidence that observation of Indian institutions had a strong

impact on the writers of the U.S. Constitution and is responsible for there

being as much democracy as there now is in the United States.17 When, following

Columbus arrival, Europeans began settling in the Americas, a movement toward

democracy was in motion in Europe supported only by the revived memory of

ancient Greece and Rome and a few isolated and scattered contemporary examples

of participatory city states. But in North America, well working democracy

was readily observable. It is undeniable that Indian political experience

directly influenced John Locke18 and Jean Jacques Rousseau,19 while Karl

Marx later developed much of his theory of human historical development on

the basis of Morgan's reports of the Seneca.20

II: The Circle Under Seige: The Impact of Colonialism on Indian Nations

to the 1960's

The onslaught, in North America, of, first, European Colonialism and, then,

United States expansion, initiated a series of devastating changes in the

circumstance of Indian nations. The United States was born into a situation

in which a number of European powers were contending for position and territory.

Until the United States obtained hegemony amongst them in North America,

the U.S. often joined in the competition to gain Indian nations as allies,

while it sought to keep formerly tribal lands, and gain new territories from

Indian nations. At least in theory, and, for a while, sometimes in fact,

the relationship of the United States to tribes was one of sovereign to

sovereign. It was based upon treaties: agreements binding both parties. As

increasingly the United States became the stronger party, during this period,

Indian nations were treated by it as protectorates. By treaty, and under

related acts, such as provisions of the Northwest Ordinance, in return for

friendship, land and, sometimes, military help, the United States had an

obligation to protect Indian lands from incursion and to provide goods and/or

money. Although the United States has often failed to live up to the treaties,

and at times has used subterfuge and coercion to obtain agreement from Indian

nations to changing their provisions, at least formally, the U.S. Government

has always recognized the inherent sovereignty of Indian nations and the

need to obtain their agreement to change treaty arrangements and obligations.21

From the outset, the United States promised to protect tribal culture and

lands and assure Indians the ability to make a living in exchange for tribes

ceding land and ending hostilities. This was the beginning of the trust

relationship between the federal government and tribal governments, which

continues to be fundamental to U.S. - Indian relations. Similarly, the inherent

sovereignty of Indian nations, with the right of self governance, has never

been extinguished, even though it was violated, in fact, by the United States

government for many years.

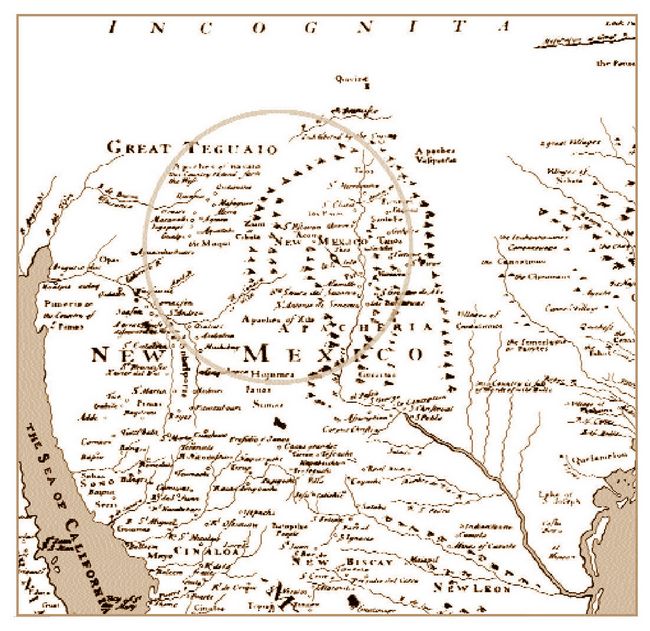

Fig.2:

John Sexton’s 1710 map showing territories of southwestern tribes

including the “Apaches of navaio” (encircled), a name commonly used by

17th-18th c. Spaniards to distinguish the Navajo from other

“Apache” tribes. The name Navajo derives from the Tewa term, Navah˙,

which refers to a large area of cultivated land (after Johnston, D.F. 1966, BAE vol.197, map 2). Fig.2:

John Sexton’s 1710 map showing territories of southwestern tribes

including the “Apaches of navaio” (encircled), a name commonly used by

17th-18th c. Spaniards to distinguish the Navajo from other

“Apache” tribes. The name Navajo derives from the Tewa term, Navah˙,

which refers to a large area of cultivated land (after Johnston, D.F. 1966, BAE vol.197, map 2).

The relationship between Indian nations and the United States has undergone

many changes.22 From the 1770's until the 1820's, prior to the U.S. becoming

the preeminent power in North America, Indian nations were treated as

protectorates, constituting sovereign nations. The U.S. Dealt with them as

legally equal political entities in international relations. With the rise

of the U.S. as the predominant power on the continent, that relationship

shifted, bringing Indian removal from the 1830's to 1850's under a variety

of treaties and Congressional acts. In this period Indian nations were treated

as dependent domestic sovereigns and dealt with on a government to government

relationship, with the U.S. having a trust responsibility to protect Indian

rights and interests. However, during this period, many Indian people were

forced to move to the west, often on terribly destructive trails of tears.23

Beginning in the 1850's until the 1930s, Indians began to be treated as wards

in need of protection, under guardianship, as the trust relationship was

interpreted by the U.S. to empower it to act however Congress decided was

"in the interest" of Indians (regardless of the actual impact of congressional

action on native people). From the 1850's to the 1870's, removal of Indians

from their lands shifted to relocation onto reservations under treaties.

In 1871 Congress ended treaty making as the United States was changing from

a policy of relocating Indians, to one of attempting to assimilate them into

mainstream culture. This policy, became full blown with the Dawes Allotment

Act, in 1887, which began the allotting of 160 acre parcels of reservation

land to individual Indians, and the sale of the remainder of the reservation

land to settlers (and in some cases, as in Oklahoma, with the termination

of reservations). As part of the process of assimilation, Indian children

were forced to go to boarding schools to learn Euro-American ways and trades.

These schools, which were often brutal in the treatment of their students,

were destructive of Indian culture, and failed to integrate Indian young

people into Euro-American society and economy. The result was that many native

young people were left alienated from both their own cultures and the wider

society.

By 1928, the Meriam Report made clear that assimilation had not been achieved

and that U.S. Policy had left Indian people in dire economic need to the

point of starvation, with poor housing, ill health, declining population,

and justifiable discont.24 Indian people and leaders had long complained

about their treatment, but as they were only a small portion of the U.S

population, generally did not have the vote until 1924, and did not gain

a full knowledge of how the American political system functioned until World

War II, they had had little power to change their situation.

Thus it was that the Roosevelt administration initiated a policy of Indian

self-government accompanied by the renewal of government-to-government relations

between the federal government and Indian tribes, who were considered

quasi-sovereigns. With John Collier leading the Bureau of Indian Affairs,

some significant gains were made toward returning Indians to self-governance

and improved living conditions. These beginning steps were put on hold by

World War II, however, and then somewhat reversed by the policy or termination

of the 1950s, that sought to end the trust relationship between Indian nations

and the U.S. Government. In effect this policy left Indians to make their

own way without any support, on the grounds that the government wasn't doing

a very good job of providing the support and empowerment it had promised,

after taking Indian lands and destroying native people's ways of making a

living. Fortunately, termination had not proceeded very far, when it was

replaced by a renewal of government-to-government relations and the trust

relationship under the present general policy of self-determination.

Thus it was that Indian renewal, seeking a return to sovereignty, self

sufficiency and harmony in Indian communities, did not fully begin until

the 1960s. By that time, American Indians had had the perseverance to survive

a horrendous physical and cultural genocide that left them facing a gauntlet

of interrelated psychological, social, economic and political problems that

they are still working to overcome today. The coming of Europeans

brought wave after wave of destructive, imperialistic intrusion, seriously

disrupting indigenous peoples' lives and ways of life. Repeatedly, Indian

population was decimated by war, imported disease (on occasion deliberately

inflicted) and harsh living condi tions resulting from relocation, reduction

of land base and destruction of traditional ways of living. By 1850, the

Indian population in the U.S., which had been estimated at 5 million in 1492,

had been reduced by 95% to 250,000.25 By 1930, tribes that were still recognized

by the federal or state governments lived on vastly reduced territory, often

far from their traditional lands, and of poor quality for providing a living,

directly through agriculture or hunting and gathering, or indirectly from

economic development. tions resulting from relocation, reduction

of land base and destruction of traditional ways of living. By 1850, the

Indian population in the U.S., which had been estimated at 5 million in 1492,

had been reduced by 95% to 250,000.25 By 1930, tribes that were still recognized

by the federal or state governments lived on vastly reduced territory, often

far from their traditional lands, and of poor quality for providing a living,

directly through agriculture or hunting and gathering, or indirectly from

economic development.

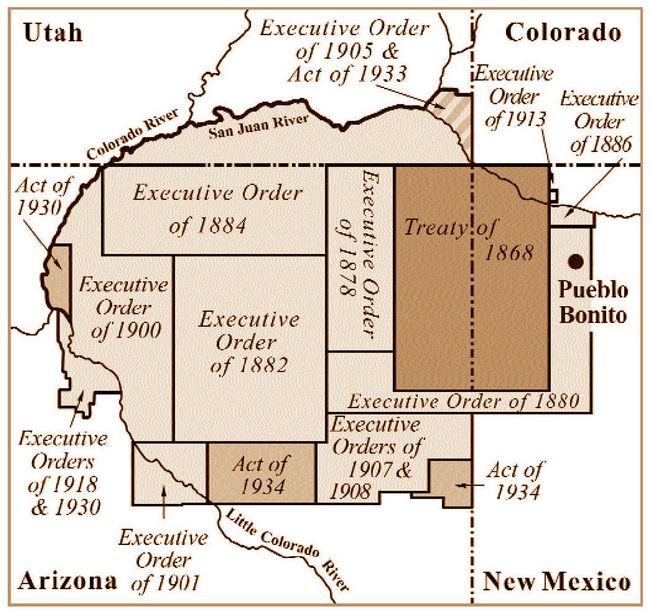

Fig.3: Growth of Navajo Reservations in the Four Corners area (after Johnston 1966, BAE vol.197).

Once proudly independent people were, thus, left dependent on the U.S.

government, which consistently failed to keep its treaty promises and trust

responsibility to provide Indian people a reasonable level of living, while

furnishing adequate material and educational assistance for Indians to regain

self-sufficiency, in return for vast cessions of land. The government's failure

to even remotely meet these "trust obligations," combined with lack of

opportunity for Indians stemming from the isolation of reservations and racist

discrimination, left them in extreme poverty.

The repeated waves of military pressure, conquest, relocation and other aspects

of physical genocide inflicted upon Indian nations from the sixteenth through

nineteenth centuries frequently caused divisions in Indian communities. Faced

with nearly impossible situations, Indian nations frequently were divided

in attempting to identify and choose the least destructive among available

harsh, high risk alternatives. Community fracturing continued under later

U.S. Indian policy that pushed indigenous people toward assimilation, although

little meaningful assimilation was possible, given poverty, limited education

and racism. This furthered the destruction of the physical basis of traditional

life and of any potential for a simple return to traditional ways. However,

di fficult as the problem of intensified factionalism was, if they had been

left free to do so, it is likely that Indian nations eventually would have

returned to community harmony in developing their own ways to adapt to the

new conditions. Though dialogue would have been more intense than usual,

the traditional values of mutual respect and the cultural mechanisms for

building consensus among diverse factions and viewpoints would have been

available to recreate unity within even the increased diversity.26 fficult as the problem of intensified factionalism was, if they had been

left free to do so, it is likely that Indian nations eventually would have

returned to community harmony in developing their own ways to adapt to the

new conditions. Though dialogue would have been more intense than usual,

the traditional values of mutual respect and the cultural mechanisms for

building consensus among diverse factions and viewpoints would have been

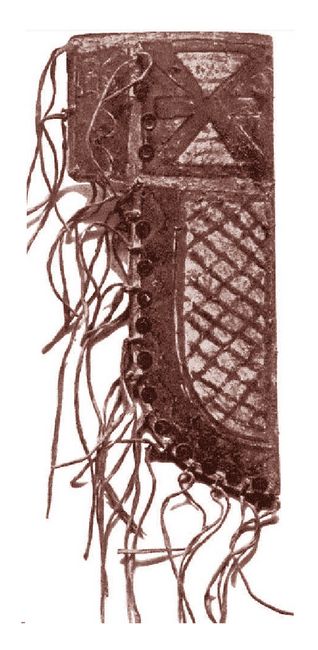

available to recreate unity within even the increased diversity.26 Fig.4 (right): Fringed knife case used in the Sun Dance by the Teton Sioux.  . .

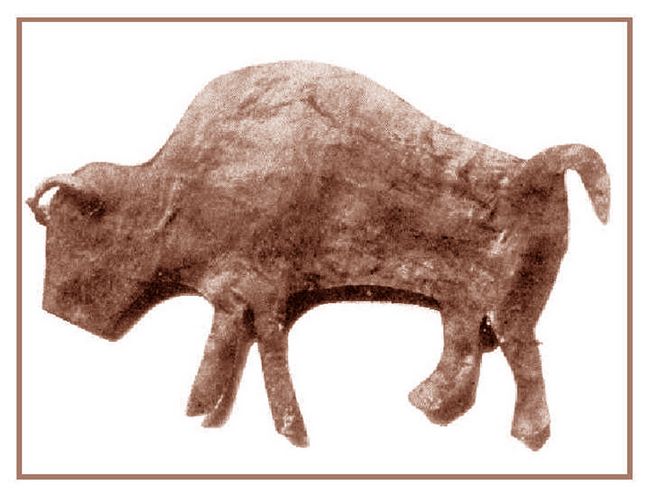

Fig.5 (left): Bison effigy used in the Sun Dance by the Teton Sioux (Densmore 1918, BAE vol.61). . At the

same time, traditional methods of spiritual and psychological healing, and

of returning individuals to inner harmony, such as the Sweat Lodge and Sun

Dance of many plains tribes (figs.4,5), and the various healing ceremonies for returning

people to beauty or harmony of the Navajo Nation, would have provided effective

means for Indian people to process and transcend feelings of historical loss

and grief.27

U.S. government policy, however, to a considerable extent, destroyed the

means that native communities had for community and individual harmonizing,

and thus considerably exacerbated community fracturing, thus furthering the

real and perceived loss suffered by individuals. This was done through a

variety of measures that undermined traditional leaders and governance, while

repressing traditional culture, including traditional religion and spiritual

practice, with the aim of assimilating Indians into "white" culture.28 Perhaps

the most pernicious of these actions was the forced taking of Indian children

from their families and communities and placing them in boarding schools

to have their traditions driven out of them.29 Since this "schooling" cut

young Indians off from their own culture, in most cases without providing

them with the ability to function effectively in Euro-American society, it

left many American Indians alienated, both from the larger culture and from

their own people.30 Often it disrupted family relationships which were the

primary supports of traditional Indian societies and cultures. Moreover,

the boarding school experience was widely marked by physical, sexual and

emotional abuse, initiating a vicious cycle of poor parenting and repeated

child abuse, in addition to creating low self and community esteem and anger

in many who suffered it.31

Moreover, the cultural genocide created new factions in many Indian communities.

For example, the disruption of traditional spiritual practice by government

policy, accompanied by the imposition of Christianity, with different

denominations sending missionaries and running schools on different reservations,

resulted in a diversification of approaches to spiritual and religious thought

and practice. While some native people have integrated the traditional and

newer ways and/or continue to be accepting of diversity, in many cases this

imposition created conflicts in values and identity.

A major aspect of the destruction of the old methods for creating community

harmony amidst a diversity of views was the U.S. government's general disavowal

of tribal self-governance, placing governance of tribal affairs in Indian

agents who, as a general rule, intentionally undermined traditional leadership

and culture. This took place to some extent under the administration of the

army, but primarily under the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) which was

transferred to the Department of the Interior in 1849.32 While the operation

of the BIA varied with time and place, and its efforts to undermine traditional

culture and values were resisted by a great many Indians, there is no question

that the BIA's administration of Indian affairs had numerous pernicious

effects,33 including increasing the degree of community fragmentation by

largely destroying the traditional vehicles for social integration and consensus

building.

The conditions of life for Indians, both on and off reservations, have improved

since 1928. Indian population has rebounded from less than 240,000 in 1900

to almost 2 million in 1990.34 However, federal spending has remained inadequate

to even approach meeting Indian needs. Moreover, since, 1986 percapita spending

for Indians has been less than that for the U.S. population as a whole, and

the gap has been widening. In 1998 federal spending per Indian was less than

65% of federal spending per American.35 The result is that from 1980 to 1990

the percentage of Native Americans below the poverty line increased from

27.5 to 30.9%. and they are now the poorest ethnic group in the United States.36

Underfunding of schools, housing, health and other services, combined with

the fact that such services are often supplied in culturally inappropriate

ways, continues to make it difficult for Indians to break out of the poverty

cycle. Of particular significance is the fact that inadequate funding and

often culturally inappropriate education have resulted in Indians having

the lowest overall rate of educational achievement of any measured U.S. group.37

American Indian health is also considerably substandard for the U.S. While

there has been a significant improvement in the health of Native Americans

over the past quarter century, they continue to have a higher mortality rate

than the U.S. population at large because of poor living conditions and a

lower availability of health care than is accorded to the American population

as a whole.38 The death rate for Native Americans (as of 1988) is higher

than for the entire population for a significant number of selected causes,39

while maternal death rates and infant mortality rates remain somewhat higher

for Native Americans than for Americans generally.40

A factor in health and in general wellbeing is the condition of housing and

of infrastructure on reservations. While conditions vary from reservation

to reservation, in general, there is insufficient housing, leading to crowding

of many people into small structures. At Pine Ridge for example, as of 1995,

there were only 1500 units for 26,000 people: an average of 17 per house,

which may be only 20' by 20.'41 About 1000 Pine Ridge residents were then

on the waiting list for housing, some of whom had been waiting for two decades.42

Much of the housing is substandard, without insulation (thus very hot in

summer, and quite cold in winter), plumbing, or an adequate kitchen. It is

aging and in serious need of repair (with the BIA housing repair program

backlogged with a documented $600 million need in 1996).43 Infrastructure,

including roads are generally seriously underdeveloped. On the vast Navaho

Reservation, with the largest Native American population in the country,

many areas are linked only by hundreds of miles of extremely poor unpaved

roads. If one wishes to enjoy Chaco Canyon National Monument, inside the

reservation, the Monument's roads are paved, but to reach it by the shortest

route from a paved highway requires a more than 20 mile drive on unimproved

road that is almost entirely washboard, threatening to shake any vehicle

to pieces that is traveling over 3 miles per hour. Other infrastructure,

such as electric power, sewerage treatment and and telephone communications

(to say nothing of fiber optic cables) are also underde veloped in Indian

country. veloped in Indian

country.

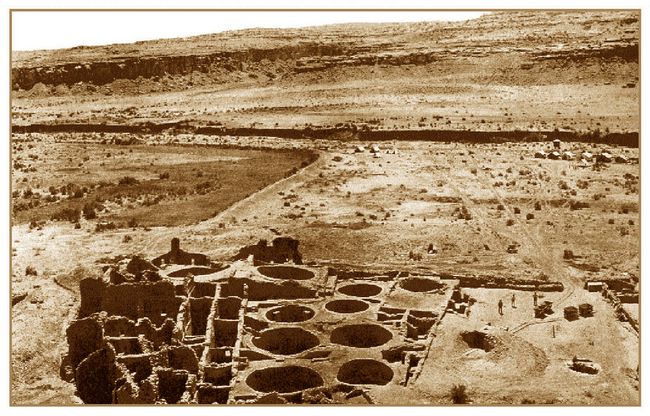

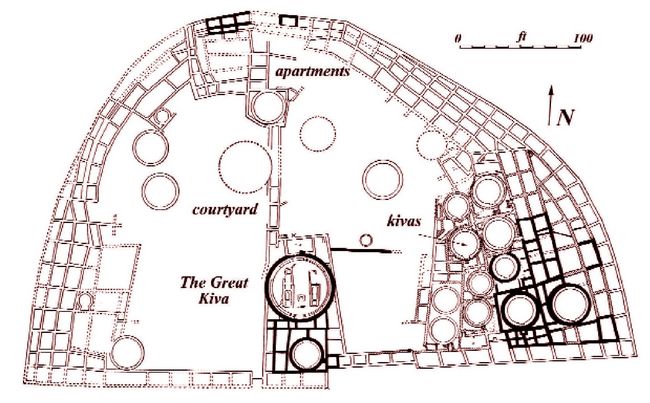

Fig.6

(above): Kivas (round subterranean ceremonial areas) in the

southeastern side of Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. This

Anasazi site, dating from the Pueblo III period (ca. 1100-1300 AD), is

within the Navajo Reservation (Judd 1924, National Geographic). Fig.7

(below): Plan of Pueblo Bonito, with about 800 residential areas or

apartments in five stories, around a central courtyard with kivas (Judd 1924, National Geographic).

The lack of adequate and appropriate education, health, other services and

infrastructure and economic development have contributed to very high

unemployment and underemployment for American Indians. Most of the available

jobs around many reservations are with the tribes, and are at least partially

funded by the federal government. There are relatively few Indians on or

off reservation in high paying jobs, such as those of doctors, lawyers or

business executives. But off reservation Native Americans have better job

opportunities than on, as is indicated in still generally relevant 1970 figures

showing that 48% of employed Native Americans in cities worked as white collar

workers, technicians, craftsmen, foremen, etc., as opposed to 35% on

reservation. While situations vary from reservation to reservation,

unemployment generally runs high, driving down wage levels for those who

can find jobs. For example at Pine Ridge in South Dakota, unemployment runs

from a low of 45% in the summer months when seasonal work, such as construction,

is available, to a high of 90% in the winter, to average about 80%.44 Over

all, unemployment for Native Americans averaged 16.2% for males and 13.5%

for females in 1989, compared to 6.4% for males and 6.2% for females in the

U.S. population as a whole that year.45

A major factor in the high rates of Indian poverty and unemployment is the

lack of economic development on reservations. Economic improvement has been

made difficult by the isolated locations of reservations and their lack of

infrastructure of all kinds. The generally low levels of education of Native

Americans is also a difficulty. Moreover, most of the limited attempts that

have been made at economic development have been undertaken in culturally

inappropriate ways that insured a high degree of failure.46 Never-the-less,

some improvement in living conditions and economic development has taken

place in recent years, largely with federal government assistance,47 but

can only continue with further external provision of resources for investment,

education and services, until the reservations become self-sufficient and

are enabled to prepare their youth to succeed in the job market both on and

off tribal lands.

The possible sources of capital necessary for the needed development of the

tribes and their members are generally limited. The lands made available

to the tribes for reservations were usually those considered least desirable

by the mostly Euro-Americans displacing tribal peoples, thus they usually

have limited potential for agriculture or ranching. In many instances the

tapping of natural resources has been possible, but must be balanced with

environmental and other concerns. Moreover, natural resources, such as oil,

natural gas, coal and other minerals are nonrenewable and can only be profitably

exploited for a limited time. Resource development has been an important

source of income for tribes, which can be increased by educating tribal members

so that the tribes can run their own resource managing operations, rather

than merely receiving royalties from outside corporations (as the Southern

Utes have done in developing their own natural gas company). Some tribes

have been able to attract some manufacturing business or start their own

businesses in various fields, either on their own or in collaboration with

external entities.48 However, given the geographic location of many Indian

nations, and the need for increased education, and other development and

services required to overcome long term poverty as well as to provide adequate

infrastructure to support development, economic advancement can only take

place over a long period of time.

One recent development that has been somewhat helpful is the rise of casino

gambling on reservations. However, for all the reasons discussed above, its

impact has generally been limited, and the myth that it has significantly

raised the fortunes of Native Americans in general is not the case. Over

all, only about 30% Federally recognized Indian nations currently have high

stakes gaming.49 In only a few cases have well located tribes and their members

become well off from gambling operations. Most casinos do not make huge profits.

Some gaming operations are extremely limited and because of location are

likely to remain so.50 Others have been important both in creating jobs for

tribal and non-tribal members and for bringing in funds and creating

opportunities for further economic development, but the needs of the tribes

are so great that these moneys, while significant, are only a small portion

of what is required. Moreover, largely because of increasing competition,

the rate of increase of profits from Indian gaming is declining, and in some

instances profits actually have declined.51 Therefore, while Indian gaming

is a significant source of capital for tribes, additional sources are needed

if Indian nations are to become economically viable, and continued federal

funding is clearly essential for tribal development.

If Indian nations and people are to solve all of the above problems, they

must be enabled to run their own lives and communities effectively. While

appropriate assistance with resources, education and technical assistance

are necessary, a primary element of Indian renewal must be a return to tribal

sovereignty through the restoration of effective Indian self-government.

Since it is not practical, at the currant time, for Indian nations to return

to being independent countries, Indian tribal governments need to be come

full partners in American federalism. There are two aspects of this development.

The first is that tribal governments be empowered to be effective. The second

is that other governments in the U.S. work with tribal governments on a true

government-to-government basis.

Governmental systems can only function effectively, producing workable policies,

when they are compatible with the values of those who live under them. From

the mid Nineteenth Century until the 1930's, the U.S. Government prevented

Indian people from governing themselves. When the Roosevelt Administration

decided to return Indian tribes to self-governance, the Indian Reorganization

Act of 1934 and the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936 imposed a Euro-American

form of representative government on many Indian nations who had no say in

how those governments would be structured. People who were used to having

a direct say in their governance had to choose those who would decide for

them. Thus, citizens were denied the basic respect of being heard directly,

which undermined their sense of self as participating members of their societies.

Moreover, tribal government has often been fractured by the development of

separate services, originally reporting to different federal agencies with

disparate regulations and reporting requirements. This tended to create competing

serfdoms, sometimes at odds with the elected leadership. These difficulties,

along with other destructive aspects of colonialism that the reform of the

1930s and 1960s was intended to overcome, often created an interrelated set

of psychological, social and political problems which feed upon each other

in creating community disharmony and a sometimes perverted public policy

process.52

In too many instances infighting has left tribal governments locked in deadlock,

or quite unstable. In extreme cases, volatile conflict relating to governance

has broken into violence, and/or led to a take over of tribal government

by the Department of the Interior to restore or maintain peace. Currently,

tribal governments are facing increasing challenges that are making community

disharmony more likely and more intense. These include demographic shifts,

rapid cultural, social and economic change, growing concerning as to whether

economic development is occurring compatibly with tribal values, and increasing

responsibility for tribal governments as the Federal government devolves

authority to the tribes, states and localities.

In recent years a growing number of Indian nations have been attempting

to make their public policy processes more effective by reshaping their systems

of governance in accordance with traditional values applied appropriately

for contemporary circumstances.53 For example, the Comanche Nation in Oklahoma,

in collaboration with Americans for Indian Opportunity, for a time increased

community harmony and overcame deadlock in tribal decision making by employing

an inclusive community discussion process to involve Comanches in considering

public issues and in democratically building consensus on policy. The Navaho

nation has been engaged for several years in decentralizing much of its

government from its tribal government to local chapters, while working to

improve the quality and extent of participation at the local level. Meanwhile,

the Southern Utes have been increasing citizen participation through a growing

number of community meetings and individual member opportunities to discuss

concerns directly with the tribal council. Thus, American Indian nations

have been working to overcome a complex of psychological, social, economic

and political problems caused by physical and cultural genocide. While much

of the necessary work must be undertaken within Indian communities, with

the assistance of appropriate outside collaboration. A major aspect of returning

native communities to wholeness is the development of mutually respectful

relations between tribal and other governments.

III: Returning to the Circle: Building Government-to-Government

Relations

When the Roosevelt Administration sought to renew government-to-government

relations with Indian nations, virtually all tribal relations were exclusively

with the U.S. Government through an extremely bureaucratic and oppressive

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).54 As head of the BIA, John Collier attempted

to have the agency give tribal governments power to make their own decisions,

while building a staff more open to Indian views by bringing a significant

number of native people into the agency. The BIA, however, found ways to

resist allowing Indian nations to make their own decisions until well into

the 1970s, while the new BIA staff were trained by the old hands, making

it a long slow process to change the culture of the agency, even when Indians

became a significant percentage of its work force.55 So it was that the first

major development in tribal self-governance came, after long protest by Indian

people and organizations, with Johnson's War on Poverty, which decentralized

carrying out of a number of federal programs to the local level with the

"maximum feasible participation" of the recipients of the program. Thus,

with the launching of a variety of programs from different agencies, in which

Indian people had a direct say, the virtual monopoly of the BIA in reservation

affairs was broken, allowing considerable nation building as tribal leaders

began to gain experience and competence in running their own programs.56

Five developments were then required to transform federal-tribal relations,

which have unfolded slowly over several administrations, are still incomplete,

and could be put on hold, or even reversed, should there be unfavorable changes

in the White House or in Congress. First, tribal governments need to be empowered

to carry out their local applications of federal programs, by being given

the legal authority, the financial and other resources, and the education

to do so. Second, there is a need for presidential leadership, and an appropriate

office or position in the White House, to coordinate federal Indian policy

with appropriate input from Indian tribal governments and urban Indians (as

more than 60% of the official members of federally recognized tribes now

live off reservation), and to insure that federal agencies and personal

understand Indian issues and people and receive Indian input on issues relating

to them. Third, there is a need for similar leadership and policy coordination

in the larger departments, such as Health and Human Services, within which

several agencies and/or divisions deal with Native Americans. Fourth, it

is necessary that, within each agency, office or division dealing with Indians,

some one knowledgeable about Indians and Indian affairs, and able and willing

to communicate with them, be appointed to coordinate Indian policy and

communications in their programs. This is a need shared with other groups

that are out side the mainstream of American middle or upper class culture,

and do not have considerable political power, as agency personnel are often

not knowledgeable about them, frequently making false assumptions about their

views, situation and needs. Fourth, appropriate executive leadership and

the development of a sensitive bureaucratic culture are required to insure

that genuine dialogue takes place between tribal governments and federal

agencies and personnel. This is but an aspect of a general problem of getting

federal agency staff to see beyond their own perspectives and genuinely dialogue

with those with whom they they interact, especially for the realization of

real government-to-government relations. State and local officials often

complain that so called "consultation" sessions with federal agency staff

too often consist largely, or entirely, in federal officials lecturing their

other government partners.

The Johnson Administration initiated what could have become an appropriate

body to coordinate Indian policy. The National Council on Indian Opportunity,

however, became lost in the concern over the Vietnam War and Johnson's winding

down his Presidency after a single term, and did not meet during his tenure.

The following Nixon Administration took some important steps toward Indian

governmental participation,57 including initiating "Indian Desks...in each

of the human resource departments of the Federal Government to help coordinate

and accelerate Indian programs."58 However, the Indian Desks were often

ineffective or of short lived value, in that many of those assigned to be

tribal liaisons already were burdened with major duties, and they often had

a low level of commitment to tribal relations. Even when the agency officer

did significant work as tribal liaison, that function was attached to that

person and not to a permanent position. Thus it was not until later, especially

in the Clinton Administration, that Indian Desks became widely established

and reasonably effective. Similarly, Nixon's coordination of Indian policy

at the White House level was informally assigned to particular advisors,

and did not continue after his term of office. Meanwhile, Congress moved

Indian self-governance ahead by passing of the Indian Self-Determination

Act in 1975, and a series of related bills.59

However, Nixon's initiatives and the inputs of Indian people inside and outside

of government did begin to bring reform in some of the larger agencies,

particularly in Health and Human Services,60 and later in the Department

of Agriculture,61 which established department wide coordination of Indian

policy and Indian liaisons in each agency within their department that regularly

dealt with Indian concerns. This later spread to other agencies, most notably

the Environmental Protection Agency.

Beginning in the 1980's, EPA created an Indian Work Group to "develop a policy

for the administration of EPA programs on American Indian Reservations" seeking

"appropriate ways in which tribal governments can play a more central regulatory

role in implementing EPA programs on reservation lands."62 EPA began hiring

qualified Indians to work in Indian related areas,63 trained its staff to

be knowledgeable on Indian issues and concerns,64 legally empowered tribal

governments and trained their staffs to run their own environmental programs.Epa,

later, obtained legislation from Congress allowing the agency to treat qualified

tribes as if they were states65 in setting first water, and later air, quality

standards for their reservations that require compliance of other government

and private entities up stream, and upwind of the reservation.

Similarly, with encouragement from the Clinton Administration, the Justice

Department has established an office to deal directly with Indian nations,

and the DOJ has instituted a number of partnership programs with tribes to

improve their justice systems. Moreover, U.S. Attorney's Offices with significant

Indian Country jurisdiction have worked with tribal, federal and state agencies

to develop memoranda of understanding to address problems of overlapping

jurisdiction.66

It is only recently that the Clinton Administration, beginning in 1994,

established what appears can become a fairly adequate and appropriate

set of mechanisms for coordination and mutual communication of concerns if

a few important changes are made to it. This began with what is believed

to be the first meeting in which all federally recognized tribes were invited

to the White House for discussion of Native American affairs.67 This has

been regularized as an annual event, forming a useful vehicle for enhancing

government-to-government relations. Going beyond that, to using it as a vehicle

for focusing upon the field of Indian affairs as a whole, it would be useful

to include representatives of "urban Indians," since more than 60% of Native

Americans now live off reservation, mostly in cities (and most federal agencies

and programs are primarily focused upon reservations).

Soon thereafter, the Clinton Administration established The Working Group

on American Indian and Alaska Natives as part of the Domestic Policy Council.

The Working Group (as of January 1997)68 was composed of 20 high ranking

members of executive departments (such as the Under Secretary of Agriculture

for Rural Development, the Chief of Staff of the Department of Commerce,

and the Principle Deputy Assistant Secretary for Congressional and

Intergovernmental Affairs of the Department of Energy) and other agencies

(such as the Office of Management and Budget), plus designated staff in each

agency, and was chaired by the Secretary of the Interior. The working group

has been the initiator, after appropriate consultation, of a number of reforms

and has taken enumerable steps to see that government-to-government relations

were operating on a regular and proper basis throughout the executive branch.

These steps included the establishment of permanent Indian desks or offices

in all agencies that regularly deal with, or have an impact upon, Native

Americans, and the drafting of several Presidential Memoranda for the heads

of agencies and departments, first "directing them to engage in continuing

government- to- government relations with federally recognized tribal governments,"

and then requesting the departments and agencies to report what

government-to-government procedures they have instituted, as a step in "insuring

that the President's directive is properly implemented."69 This has led to

a continuing of federal agency development of Indian consultation during

the early days of the Bush administration, even though President Bush is

not particularly oriented toward the government-to-government approach of

the national government in dealing with Indian Issues, and may move to reverse

some of those policies.

There is, however, one major problem with the Clinton Administration's

organization of the Working Group. It was headed by the Secretary of the

Interior. Institutionally, this presented the Secretary with a conflict of

interest between his responsibilities to his department and the requirements

for coordinating Indian policy as a whole. He had pressures from a number

of constituencies in his department, along with concerns for maintaining

his power and authority to function effectively as department head. Moreover,

the Secretary of Interior, as an equal with other department heads, must

regularly work cautiously and diplomatically with other departments. As a

result of this duel difficulty, energy was drawn away from the Secretary's

seeing that the BIA and other Interior agencies dealt adequately with current

major issues and communicated well with the tribes. As a result, the Working

Group was unable to move swiftly or effectively to solve major problems that

crossed departmental and agency jurisdictional boundaries in such crucial

fields as gaming and the handling of toxic wastes. Moreover, little was done

to improve the extremely varied quality of tribal communications infrastructure,

so that all tribal governments and their members could receive up to date

information from, and provide timely input to, all federal agencies (as could

be achieved through developing adequate internet linkages). What needs to

be done is to move the coordination (and chairing) of the Working Group entirely

into the White House as part of the Intergovernmental Working Group with

equal status for tribal governments with state and other governmental entities.

Here it will be able to operate from above the level of the departments with

a clear institutional interest in, and the full authority to effectively

coordinate Indian policy and its implementation in dialogue with the Tribes.

Meanwhile, the decentralization of federal programs to tribes through block

grants became a general policy of Congress and the Clinton administration.

For example, HUD has decentralized all tribal housing programs to tribally

run housing authorities through direct block grants under the United States

Housing Act of 1996.70 As Congress has been devolving federal programs to

the states, to date, it has provided for tribal governance of Indian portions

of programs and/or collaboration between tribal and state governments in

program administration. For example, in enacting welfare reform under P.L.

104-193 in 1996,71 which moved welfare financing and administration to providing

direct block grants to the states for welfare, Congress provided the possibility

that in many instances tribes could take over programs, directly receiving

federal funding. Under some circumstances, however, this leads to a reduction

in program funding to the tribe. As an alternative, Congress has included

some incentives for states to make compacts with tribes to provide tribal

programs, most likely at the same level, or close to the same level, as is

provided to the rest of the state. Generally, the impact of welfare reform

is to reduce assistance to low income persons. In some cases the reductions

in the act fall more lightly upon some tribes, but more generally, the impact

has been heavier on tribes than upon states, depending on the relevant provisions

of the legislation and how the reform has implemented in practice. What is

clear, is that when the national government delegates programs to the states

that affect Indian tribes, that the legislation needs to include adequate

incentives and mechanisms to be sure that Indian people are treated fairly

and that states will consult fully with tribal governments to insure that

the Indian portions of programs operate adequately and appropriately. This

was not entirely the case with welfare reform, although it did promote some

well working tribal-state cooperation.72

An attempt to carry decentralization of federal programs to Indian nations,

to the greatest degree possible, was begun during the Clinton years under

"The Tribal Shares Process."73 The Bureau of Indian Affairs, acting under

the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act and Fiscal Year

1997 Appropriations Language for the Department of the Interior, worked with

every federal agency involved with Indian nations, and received public comment,

including from Indian tribes, to develop a list of: 1) those functions in

Indian programs that are inherently federal (IFF), and can only be carried

out by the federal government, and those functions that are non-inherently

federal that can be carried out by tribes directly, or if the tribes are

unable or unwilling to carry them out themselves, can be contracted out by

the tribes. It remains to be seen how appropriate the division of functions

is in the list as it operates in practice. What is clear, is that there was

an increase in the percentage of federal Indian program money going directly

to tribal governments and in the extent to which Indian tribes run or contract

out federal programs.74

It should be noted, however, that the number of Indian Nations taking over

federal programs coming to them under all of the methods available is only

increasing very slowly. The problem is, first, that many of the tribes are

not yet equipped to handle their own programs, and there is insufficient

federal assistance to prepare them. Second, many tribes do not yet have the

administrative structures necessary to carry out programs that could be turned

over to them. Third, since the current arrangements merely shift monies from

the federal government to the tribe, without reimbursement for the added

administrative costs for the tribe, there is little incentive for tribes

that are uncertain of their ability to take on the considerable responsibility

to administer federal programs and monies, to move to begin to do so. Moreover,

the Clinton Administration initiated little after 1996 that might concretely

further enhance government-to-government relations, and the Bush administration

is not likely to take further steps in this direction. Finally, there remain

instances of bureaucratic resistance or inertia in which federal agency personnel

fail to complete contracting or turning over of specific functions to tribal

governments.75

The devolution of authority from the federal government to tribal governments,

and more recently to state and local governments, has brought about an increase

in tribal-state and local government relations.76 Until the 1970's, such

relations were limited, and largely marked by a costly competition for

jurisdiction, following from mistrust and misunderstanding, sometimes marred

by racism. As tribal governments have gained authority and competence, they

have been better able to collaborate with neighboring governments. The increase

in tribal government competence, combined with a more favorable public view

of Indians, and a rise in Indian political power 77 have contributed to the

willingness of state and loc al governments to collaborate with states. Moreover,

as reservation economies have improved, while a number of studies have shown

that Indian people contribute significantly to the economies of their areas

and states while paying more in state and local taxes than they receive in

benefits,78 citizens and policy makers have gained a growing understanding

that they have an interest in working cooperatively with Indian nations. al governments to collaborate with states. Moreover,

as reservation economies have improved, while a number of studies have shown

that Indian people contribute significantly to the economies of their areas

and states while paying more in state and local taxes than they receive in

benefits,78 citizens and policy makers have gained a growing understanding

that they have an interest in working cooperatively with Indian nations. Fig.8: Bidaz-Ishu, a Chiricahua Apache (BAE 43).

There are numerous examples of increasing collaboration between state and

local and tribal governments in many fields.79 For example, in order to deal

with the difficulties of complex law enforcement jurisdictions on and around

checkerboard reservations (where jurisdiction is different depending whether

the alleged offence takes place on or off reservation land, and whether the

alleged violator is Indian or non Indian), a number of tribes, including

the Southern Utes in Colorado, the Miccosukees in Florida, the Blackfeet

in Montana and the Yakimas in Washington, have found effective solutions

to these difficulties by coming together with neighboring local and state

police to cross deputize each other's officers (so that they have authority

in each other's jurisdictions) and to engage in close communication and

collaboration.80

Similarly, where issues of taxation have often found tribal and state and

local governments in conflict, in South Dakota, the state and the Oglala

Sioux have worked out an agreement on the tribal sale of cigarettes. Legally,

the state can only tax sales to non-Native Americans while the tribe can

tax all sales. In this case the state and the tribe have set the taxes so

that tax payment is equal. The state collects all the cigarette taxes on

the reservation, and then, after deducting a small administrative fee, passes

the tribe's share on to the tribe. A number of other tribes have made similar

agreements with the states.81

A particularly advanced example of tribal-state collaboration, involving

the coming together of several Indian nations with multiple agencies in three

states to discuss common problems and develop policy, is the ongoing dialogue

between the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board and the states of

Idaho, Oregon and Washington over health care policy.82 The Board, representing

many of the tribes in the three states since 1974, has a professional staff

and actively communicates with member tribes; state, regional and national

Indian Organizations concerned with health issues; and health related agencies

in the three states. A major factor in the success of the collaboration is

that each state has developed its own vehicle for coordinating health policy

and dialoging with the tribes in the state. In Oregon and Idaho representatives

of tribal governments meet regularly with the state's coordinating institution.

In Washington, the concerned tribes formed the American Indian Health Commission

for Washington State to provide policy advice and collective communication

with the state on health matters. It communicates regularly with a variety

of state and local health agencies, while each Washington tribe appoints

its own representative to the Indian Policy Advisory Committee in the Washington

Department of Social and Health Services. The department also has appointed

a liaison person for Native American/Alaska Native issues who is actively

involved with the Commission, playing an instrumental role in avoiding and

solving problems. Thus by providing professional staff and an active information

and dialoging network, a well working relationship for the mutual development

of policy and resolution of problems has been established. The Pacific Northwest

health policy collaboration is a particularly important precedent for the

realization of effective tribal state partnerships. The key element, which

is often missing when tribal and state and local governments would like to

collaborate, is the institutionalization of effective means of communication

and policy coordination along the lines that the federal government has been

moving toward.

IV. What Is Necessary for a Full Return to the Circle

For Indian nations to return fully to sovereignty, self-sufficiency and harmony

as partners in American federalism, the entire range of problems relating

to Indian communities and people that were brought on by physical and cultural

genocide must be fully and properly addressed. First, there are a variety

of psychological problems that afflict many Native Americans including:

unresolved historical loss and grief, low individual and community esteem,83

and a number of patterns of thinking and associating, developed as adaptations

to destructive conditions, which are in need of transformation. All of these

wounds must be healed for a return to individual and community wholeness

and harmony. Second, are a number of related social problems including the

highest rate of alcoholism and other forms of substance abuse of any U.S.

ethnic group,84 various forms of abuse of self (including very high suicide

rates 85) and others (both physical and emotional),86 a violent crime rate

more than twice the national average 87 and the lowest rate of educational

achievement and the highest school drop out rate of any U.S. ethnic group.

Third, are a set of political problems including lack of appropriate forms

and processes of self-government, an incomplete return to sovereignty and

self-determination in relation to other governments, and often a lack of

a sufficient number of adequately educated people for full self-determination

with well operating self-governance.88 Fourth, is a set of economic problems

including a lack of sufficient resources for creating individual and community

self-reliance, and for providing the needed, appropriate education and other

services necessary to solve the entire set of difficulties confronting Indian

communities and their members.89 The accomplishment of this set of tasks

will not benefit Indian people alone. The development of Indian communities

since 1960 shows clearly that, as Indian people take control of their own

lives, they improve their condition, allowing them to contribute significantly,

economically, socially, politically and spiritually to the well-being of

the people living around them and of the entire nation. The struggle to complete

American Indian renewal is a concern for all Americans.

. .

[Editorial note: The printed version of the article, published in two parts

in Athena Review (Vol.3, no.2, pp. 90-97, and Vol.3, no.3), was

in places (especially in the footnotes) edited for the sake of brevity, in

order to fit into the available pages. The present web version is complete,

containing the full set of footnotes as well as the full text of the article.]

.

FOOTNOTES

1. Several authors have delineated a set of "pan-Indian" values. These have

included generosity, respect for elders, respect for women as life-givers,

regarding children as sacred, harmony with nature, self-reliance, respect

for choices of others, accountability to the collective, courage, sacrifice

for the collective in humility, recognizing powers in the unseen world, and

stewardship for the Earth. See A. Timas and R. Reedy, "Implementation of

cultural-specific intervention for a Native American Community," Journal

of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1998, pp. 382-393.

2. Sharon O'Brien, American Indian Tribal Government (Norman: University

of Oklahoma Press, 1989), CH. 2,; and Stephen M. Sachs, Rembering the Circle:

The Relevance of Traditional American Indian Governance for the Twenty-First

Century," Western Social Science Association Meeting, Reno Nevada, 2001.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. For an example of this concerning the Cheyenne, see E. Adamson Hoebel,

The Cheyennes: Indians of the Great Plains (New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston,

1960), p. 37.

6. See Morris Edward Opler, An Apache Way of Life: The Economic Social, and

Religious Institutions of the Chiricahua Indians (Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1996), on politics, particularly pp. 460-471.

7. This general pattern of mutual obligation and mutual support was a common

element of precolumbian American Indian society, although the detailed form

of family and social structure varied from tribe to tribe, and within a tribe

over time. Ella Deloria, Speaking of Indians (Lincoln, University of Nebraska

Press, 1998), Part II, "A scheme of Life That Worked," pp. 24-25, says of

Dakota interpersonal relations what was widely the case: Kinship was the

all-important matter. Its demands and dictates for all phases of social life

were relentless and exact; but on the other hand, its privileges and honorings

and rewarding prestige were not only tolerable but downright pleasant for

all who conformed. By kinship all Dakota people were held together in a great

relationship that was theoretically all-inclusive and co-extensive with the

Dakota Domain. Everyone who was born a Dakota belonged in it; nobody need

be left outside. [And since being Dakota, as with Indian societies generally,

was more a matter of participation in the community than blood, kinship included

all who effectively joined the community, whether they married in or were

adopted, a common practice throughout traditional Native America].

". . . I can safely say that the ultimate aim of Dakota life, stripped of

accessories, was quite simple: One must obey kinship rules: One must be a

good relative. No Dakota who has participated in that life will dispute that.

In the last analysis every other consideration was secondary-property, personal

ambition, glory, good times, life itself. Without that aim and the constant

struggle to attain it, the people would no longer be Dakota in truth. They

would no longer be even human. To be a good Dakota then was to be humanized,

civilized. And to be civilized was to keep the rules imposed by kinship

for achieving civility, good manners, and a sense of responsibility toward

every individual dealt with. Thus only was it possible to live communally

with success; that is to say, with a minimum of friction and a maximum of

good will."

For a similar view from a Cherokee perspective, see Michael Garrett, "To

Walk in Beauty: The Way of Right Relationship," in J.T. Garrett and Michael

Garrett, Medicine of the Cherokee: The Way of Right Relationship (Santa Fe:

Bear and Company Publishing, 1996), p. 165-166.

8. Clyde Kluckhohn and Dorethea Leighton, The Navaho (Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1974), pp. 111-123. Robert W. Young, A Political History

of the Navajo Tribe (Tsaille, Navajo Nation, AZ: Navajo Community College

Press, 1978), pp. 15-16, 25-27, reports that, according to Dine legend, the

people lived in independent, self sufficient camps, in which, like other

band societies, discussed below, decisions were made by the community by

consensus. Headman (Hozhooli Naat'aah) only acted as advisors. He usually

was proficient in leading at least one ceremony, governed by persuasion,

"expounded on moral and ethical subjects, admonishing the people to live

in peace and harmony. With his assistants he planned and organized the workday

life of his community, gave instruction in the arts of of farming and stock

raising and supervised the planting, cultivating and harvesting of the crops.

As an aspect of his community relations function, it was his responsibility

to arbitrate disputes, resolve family difficulties, try to reform wrong doers

and represent his group in its relations with other communities, tribes and

governments. He had no functions whatsoever relating to war because the conduct

of hostilities was the province of War Chiefs. " A headman was a man of high

prestige, chosen for his good qualities and only remained a leader "so long

as his leadership enlisted public confidence or resulted in public benefit."

9. Kluckhohn and Dorethea Leighton, Ibid., p. 118.

10. Ibid., p. 120.

11. Laura E. Klein and Lillian A. Ackerman, "Introduction," and Daniel Maltz

and JoAllyn Archambault, "Concluding Remarks,", in Laura E. Klein and Lillian

A. Ackerman, Ed., Women and Power in Native North America (Norman: University

of Oklahoma Press, 1995), pp. 3-16 and 230-249.

12. O'Brien, American Indian Tribal Government, pp. 17-20.

13. Valerie Sherer Mathes, "Native American Women in Medicine and the Military,"

Journal of the West, Vol. 21, 1982, p. 44.

14. Klein and Ackerman,Women and Power in Native North America. The one exception

in the study was the case of the Muscogee, and this was a partial exception

both concerning the place of women in particular, and the relative lack of

hierarchy in Indian societies, in general.

15. As explained more fully in Ibid., while men and women did not do the

same things, or have the same authority and power, their was a balance in

their relations referred to as "balanced reciprocity." Concerning the one

case, that of the Muscogee, reported in Ibid. not to involve balanced

reciprocity, Joyoptaul Chaudhuri, who was married to a Muscogee woman and

lived amongst them and studied their tradition for 40 years, commented to

this author that that conclusion is only accurate for post contact times

and not for the pre-contact Muscogee, which is no longer known by many tribal

members. That the traditional Muscogee maintained a balance between men and

women, see Jean and Joyotpaul Chaudhuri, A Sacred Path: The Way of the Muscogee

Creeks (Los Angeles: UCLA American Indian Studies Center, 2000).

16. Katherine M. B. Osburn, Southern Ute Women: Autonomy and Assimilation

on the Reservation, 1887-1934 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press,

1998), p. 23 states,

" In short, before confinement to the reservation, the Utes recognized

significant differences in gender roles but did not value one gender more

highly than the other. Women were equal members of their families and bands.

They did not restrict their activities to the home and allow men to rule

in the public realm. Rather, they participated in councils, were active in

warfare, and provided leadership and power in spiritual matters. After relocation

to the reservation, women continued to insist on participation in public

affairs."

17. See Bruce Johnson, Forgotten Founders: How American Indians Helped Shape

Democracy (Harvard and Boston: The Harvard Commons Press, 1982; Donald A.

Grindle and Bruce E. Johnson, Exemplar of Liberty: Native America and the

Evolution of Democracy (Los Angeles: American Indian Studies Center, UCLA,

1991), including Vine Deloria's introduction discussing the issues of scholarship

on this question; Jose Barreiro, Ed., Indian Roots of American Democracy

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992); and in Lyons, et al, Exiled in

the Land of the Free, see, Mohawk, "Indians and Democracy," Robert M. Venables,

"American Indian Influence on the Founding Fathers," and Donald A. Grinde,

Jr., Iroquois Political Theory and the Roots of American Democracy."

18. The Second Treatise on Civil Government, #108 (p. 61) & #184 (p.

102).

19. Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract (New York: E. P. Dutton and

Co., Inc., 1950), Book Ill, Ch. V (p. 67), and indirectly on the subject

of confederacy as a new subject in reference to the Six Nations or Iroquois

league and other native American confederations including the Huron, Book

Ill, Ch. XV (pp. 96-97 in the footnote). Rousseau also commented favorably

on Native American life in, "A Discourse on the Origin of Inequality" published

in the same volume.

20. T. B. Bottomore, Karl Marx: Selected Writings in Sociology and Social

Philosophy (New York: McGraw-HilI. Book Company, 1964) Introduction at p.

39. Marx and Engles had read L. H. Morgan, Ancient Society. For a discussion

of the limitations of Morgan's understanding, see Joy Bilharz, "First Among

Equals? The Changing status of Seneca Women," in Laura F. Klein and Lilillian

A. Ackerman, Women and Power in Native North America (Norman: University

of Oklahoma Press, 1995), p. 107.

21. Vine Deloria, Jr. and David E. Wilkins, Tribes, Treaties, and Constitutional

Tribulations (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999), particularly Ch.

3. See p. 61 for a discussion of the basic standards for valid treaties,

and acts following from them, between the United States and Indian Nations.

22. The stages and related history are discused in O'Brien, American Indian

Tribal Government, Part 2, and Ch. 12. A more detailed history is presented

in Angie Debo, A History of the Indians of the United States (Norman: University

of Oklahoma Press, 1970), Ch. 2-21.

23. As with the Cherokees (Debo, Ibid., pp. 120-125), the Muscogee (or Creek)

and Seminole (Ibid., pp. 116-120, 125-126; and Chaudhuri and Chaudhuri, The