|

by Patricia Grimshaw

.

Ships came from east-way,

All eager for battle,

With grim gaping heads

And rich carved prows.

They carried a host of warriors.

(Snorri Sturluson, Saga of Harald Hairfair, Ch.18)

Since the Merovingian Age of the 6th-7th centuries AD, Norsemen have been associated with ships - for trade, exploration, and

of course war. Seafaring entirely permeated the mental life of the

Norse. The trade routes brought wealth to artisans; explorers of the

early Middle Ages returned with tales of exotic lands;

the warships, with dragon prows slicing through the waves, brought home

brave warriors, conquering heroes, and many riches. No aspect of Viking

life was entirely separate from the influence of ships, including

death, and the heroic deeds of many have survived to our own day

through epics and sagas.

Fig.1: Dragon head post from the Oseberg ship burial (Viking Ship Museum, Oslo)

The greatest details regarding early Scandinavian history come from the

writings of the Icelandic chronicler Snorri Sturluson, who composed the

Heimskringla (History othe Kings of Norway) sometime between AD 1220

and 1235, plus numerous other works. The record of the Heimskringla

goes back to prehistoric eras, beginning with mythology and quickly

becoming a relatively clear and vivid source. In this huge document,

Snorri mentions at least 2,000 place names, and the personal names of

some 1,300 individuals. Although much is lost in modern

translations, the original poetry of the sagas remains on many levels,

and historians are ever grateful to their predecessor for his attention

to detail.

For about four centuries, the sagas

and legends were meticulous in their portrayal of ships. The tale of

King Olav Trygvason relates in detail the ship upon which he sailed:

. . .it was a dragon ship and made after the model of the Serpent, which the king

had brought from Hålogaland. But the new ship was much bigger and

in all things more splendidly fitted. This vessel he called the

Long Serpent, and the other the Short Serpent. In the Long

Serpent there were thirty-four rowing seats. The head and the

crook at the stern were all gilded and the bulwarks were as high as an

ocean-going ship. That was the best fitted and the most costly

ship that was ever built in Norway (Snorri Sturluson, Saga of Olav

Trygvason, 88).

This documentation, of course, may have been embellished for the sake of a good story.

In addition to the legends, there is visible evidence; handfuls of ship

burials have been discovered in the past two centuries, such as those

at Gokstad and Sutton Hoo. Therefore, we can use both the

archaeological and the literary evidence to piece together a small

window into the world of the Vikings. It is particularly interesting

that the ships that do remain to this day were buried, an intriguing

practice which, due to its pagan implications, died soon after the

Viking conversion to Christianity.

It must be clarified, before continuing further, that much like other cultures, the

epics, sagas and fireside stories that permeated Viking, Norse and

Icelandic civilizations dealt only with the upper echelons of society.

Peasants, slaves, and other “lower class” individuals were rarely, if

ever, outlined in epics, except perhaps as minor characters whom the

hero(s) had met. Epics and sagas were tales of pride and grandeur.

Naval power, perfected early by Norsemen, had an exceptional place in

these tales, and continued to be used in Christian narratives after the

Conersion.

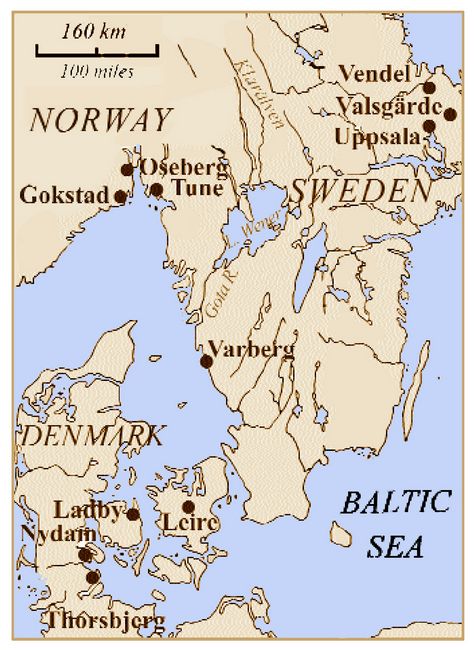

Fig.2: Map of Viking ship burials in Scandinavia (after Green 1963; Logan 1983).

There is not a great deal in the way

of iconographic evidence for the earliest period of boat building by

the Nordic people, but the record does increase from about the 11th

century AD until the end of the Viking era. There is also

literary evidence, present in many heroic sagas, of the abundance of

Viking exploration and acquisition of land, beginning in about the 9th

century (Illsley, 1999). The most valuable evidence, however,

undoubtedly comes from archaeology.

The sites

dating from the Viking age that are most commonly investigated by

archaeologists are graves. These sites have been found virtually

everywhere the Vikings settled, including the Isle of Man at

Balladoole, Knock y Doonee and Sronk yn Howe; and of course

in Scandinavia at Oseburg, Ashby, Ladby and Gokstad (fig.2).

Anglo-Saxon sites at Sutton Hoo and Snape in southeast England predate

the Vikings, but they do have Swedish connections (see AR,2,2 on Sutton

Hoo).

In archaeological terms, the survival of

a boat burial depends entirely upon the soil in which it was interred.

For example, soil that surrounded the early 7th century AD find at

Sutton Hoo is highly acidic, thus all that remained of the original

vessel were the rivets in a ghostly outline. Nevertheless, this,

combined with previous knowledge of Viking boat construction, sagas,

and other finds, allows us to determine how the ships were produced.

The Nydam oak boat, found in 1863 in Southern Jutland, dates from the

fifth century and is a precursor of the characteristic long boat

associated with the height of the Viking period (Illsley, 1999). It

cannot, however, necessarily be classified as a Viking ship as the

Vikings themselves did not yet exist at that time. The boat was

constructed with planks laid so that the lower edge of each one

slightly overlapped the one below, but was rivetted with iron nails

(Brøgger, Shetelig, 1971). The Nydam oak boat, measuring 76 ft overall

was most likely a warship, in a period when there was no real

difference between warships and trading vessels, a result of the low

rate of economic activity in early Scandinavia (Illsley, 1999). This

formation of boat would improve until its climax in the Gokstad ship.

As the Norsemen expanded further into Europe, two crucial additions

were made to the structure of their ships around the seventh century: a

heavy T-section keel, and the use of a single mast, with a square sail

(Illsley, 1999). The Vikings also decorated their ships with

fearsome figureheads:

Fair maid! The noble ship was

Borne forth from the river to the sea.

Mark where the long body of the dragon

Lies off the land.

The dragon's gold-green mane

Shines o'er the deck; the neck

Borne burnt gold. Then

It glided from its moorings.

(Snorri Sturluson: King Harald's Saga, Ch. 60).

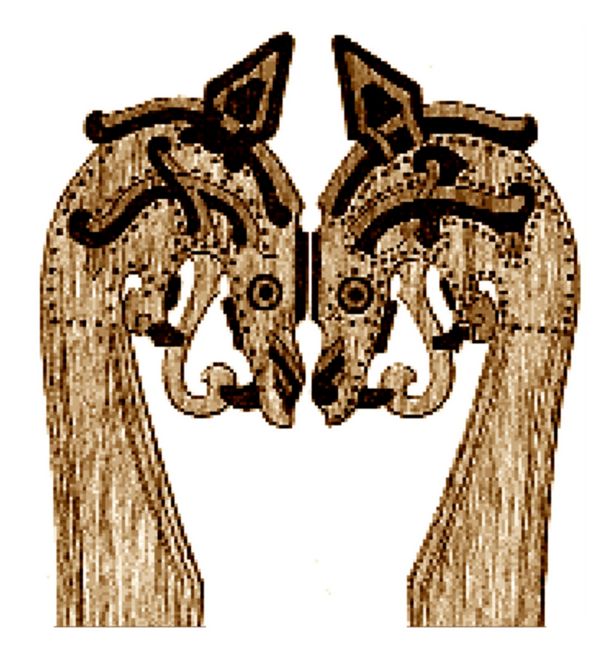

Fig.3: Dragon heads from Gokstad ship burial; part of verge boards for a tent (Nicolaysen, 1882, Plate XI).

These symbols have become rather stereotypical of the era to our own

society, and they were intended to inflict great fear in the Vikings'

enemies. Because the ships were often adorned with dragons (figs.1,3),

the larger ones were referred to as Drakars (Drage meaning dragon and

Kar, ship) with the smaller vessels being known as Snekkars (Snag

meaning snake; Illsley 1999).

This

psychological ploy of the Norsemen apparently worked, as it was

mentioned in the Encomium Emmae Reginae, Richard I ducis Normannorum

filiae (“In Praise of Queen Emma, daughter of Richard I, Duke of

Normandy”), a biography commissioned between AD 1040 and 1042 of Queen

Emma’s Danish dynasty, providing an almost contemporary view of several

of the characters which appear in Scandinavian history (Campbell 1949).

The work also describes Norse ships, noting that many were decorated

with heads and forms of various creatures:

"On

the sterns could be seen different faces of metal ornamented with

silver and gold. On one the statue of a man, on another a golden lion,

and on a third a dragon of bronze, on a fourth an enraged bull with

gilded horns. These awful faces, together with the shining bucklers of

the soldiers, and their polished weapons, spread terror into the souls

of those who saw them. "

(Encomium Emmae, as cited in Illsley 1999).

Similarly, the Bayeux Tapestry (AR I,3 p.13) depicts the double-ended

ships, adorned with figures, in which the Normans (descended from the

Norsemen) sailed to England with their leader, Duke William of

Normandy, and conquered the Anglo-Saxons in AD 1066.

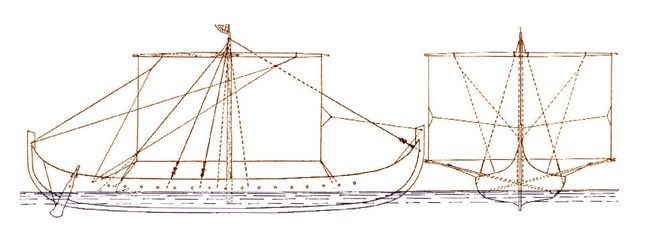

The Gokstad ship, found in 1880 in Sandefjorde, Norway, is 79 ft overall, double-ended, like all Nordic ships, with a high curving stem

and stern posts (fig.4). The remains of the mast fitting suggest that

the original would have been about 42 ft high, making the ship rather

powerful and swift in the water. The Gokstad ship was also recovered

with the shields attached to the gunwale, at the ready for the warriors

on  board. The technical perfection of this ship comes as a result of a

long tradition of experience and experiment that first yielded sailing

ships suitable for the open seas about one hundred years before the

Gokstad ship was even built (Sawyer, 1971). board. The technical perfection of this ship comes as a result of a

long tradition of experience and experiment that first yielded sailing

ships suitable for the open seas about one hundred years before the

Gokstad ship was even built (Sawyer, 1971).

Fig.4:

Rigging of the Gokstad ship (ca. AD 880) based on the reconstruction

proposed by Harald Akerlund in Unda Maris, 1955-56, with a shorter mast

(after Sawyer 1971).

Finally, the Ladby ship, believed to date from the 10th century, was

unearthed in 1935 on Funen, Denmark. Like the ship at Sutton Hoo, the

wood skeleton had disintegrated, leaving an impression in the soil.

From this feature, archeologists were able to determine that the vessel

was 67.5 ft long and 9.5 ft wide, much smaller than the Gokstad ship,

but closer in length to beam ratio (1:7) for a fast-oared warship

(Illsley, 1999). Not only does this boat more neatly parallel the

standard Viking warship, but it is also thought to be equivalent to

those used by William, Duke of Normandy, in 1066 and portrayed on the

Bayeaux Tapestry.

In the Ladby ship a nobleman's

body was uncovered, together with 11 horses and several dogs. One of

the nobleman's horses bore an elaborate harness, and many other

artifacts were unearthed, including a game board, arrows and a shield

(Ladby Ship Museum, 1999). The ship was also “roofed” over with

close-fitting, he avy planks before being covered by earth. Despite the

Ladby ship's representation of the general warship, it was most likely

meant to be used for ceremonial show rather than serious warfare

(Illsley, 1999). avy planks before being covered by earth. Despite the

Ladby ship's representation of the general warship, it was most likely

meant to be used for ceremonial show rather than serious warfare

(Illsley, 1999).

Boat burials in combination with sagas

indicated that Viking activity, whether trading or raiding, depended

upon reliable ships to sail, and without them the longer sea crossings

that we know to have occurred (to Iceland, Greenland, and L'Anse aux

Meadows in Newfoundland, for example) would have been impossible. These

boats gave the warbands the advantage of surprise, as well as a brisk

getaway. The voyages that had become commonplace in the 9th century

would have been incomprehensible 100 years earlier.

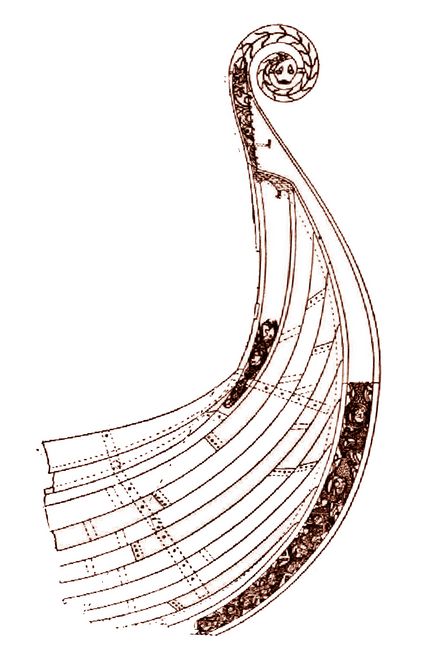

Fig.5: Prow of the Oseberg ship (after Brøgger and Shetelig 1951).

When the scholarly monk Alcuin (who was educating nobles at the court

of Charlemagne at the time) first learned of the Viking raid on the

monastery at Lindisfarne in AD 793, he wrote a letter to King Æthelred

of Northumbria, stating:

“It is nearly 350 years that we and our fathers

have inhabited this most lovely land, and never before has such a

terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race,

nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made” (as

cited in Sawyer, 1971).

This attack,

seen as an affront to civilization itself, made certain that the

Norsemen would forever imprint their image on the minds of those they

vanquished, an image which continues to this day.

Together with their travels upriver and across the open ocean, the

Vikings saw death as a great voyage - another sortie into unknown

territory - in which water needed to be crossed. As a result, several

great Viking leaders took their boats with them after death. The sagas

note many ship funerals in either of three forms: cremation of the

entire ship and noble, after which an outline was often marked in the

ground as a memorial; setting the ship alight and letting it float out

to sea, as the lone passenger embarked on his final journey; and

finally the ship burial with which a ship and its contents would be

interred, sometimes with a body, sometimes with only the ashes of the

deceased.

The Vikings treated

their mortal warriors with as much reverence as their deified ones, and

this is evident in Norse mythology, particularly with the tale of

Balder. This god of light was killed by a “dart of mistletoe” thrown by

the mischievous Loki, resulting in “the greatest misfortune ever to

befall gods and men” (Snorri Sturluson, Prose Edda). Balder was

afforded a lavish funeral recorded in Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda,

written around the same time as the Heimskringla:

[They] took

Balder's body and carried it down to the sea. Balder's ship was called

Hringham [Ringhorn], it was a very large ship. The gods wanted to

launch it and to build Balder's funeral pyre on it, but they could not

move it at all... ... Then Hyrrokkin went to the prow of the vessel and

at the first shove launched it in such a way that the rollers burst

into flame and the whole world trembled ... Balder's body was carried

out onto the ship, and when his wife Nanna, daughter of Nep, saw that,

her heart broke from grief and she died. She was carried onto the pyre

and it was set alight.

This sea-borne ship would carry Balder to his destination until, as the Norse believed, he would come again.

These were pagan rituals, however, and this has bearing upon how they

were described, or not, in the sagas. Notably, Christianity became the

official religion of Iceland during the Saga Age itself; the religion

was accepted by the General Assembly of Iceland in AD 999 (Schach,

1984). At this time, the Icelandic people had an oral culture. When the

sagas were written during the 13th century, the country had been

Christian for more than 200 years (Hallberg, 1962); therefore, it is

not surprising that the belief system had left its mark on the

literature, and had obliterated a great deal of the previous pagan

rituals that would have been known to us had the conversion come a

century or two later. The practice of ship burials is one such rite.

Ship funerals, however, are mentioned with relative frequency in

Icelandic sagas, as are human burials near the sea. In Eyrbyggja Saga, the nobleman Arnkel fought with the priest, Snorri, and was killed. The saga relates:

Arnkel's

men took his body and laid it out for burial. A mound was raised for

him at Vadilshofdi close by the sea, as large as a great haystack... (Pálsson and Edwards, 1989).

Like the burial at Sutton Hoo, in which the ship was located looking

out over a bluff towards the sea, Arnkel's followers recognized the

importance of the location to their leader, and placed him there with

great consideration.

This rite was not restricted to men by any

means, and the sagas also note this. For example, the Laxdaela Saga

recites the wedding of Olaf “Feilan” in AD 920. The feasting, however,

is interrupted by the death of a guest:

The

day after, Olaf went to the sleeping bower of Unn, his grandmother, and

when he came into the chamber there was Unn sitting up against her

pillow, and she was dead. Olaf went into the hall after that and told

these tidings. Every one thought it a wonderful thing, how Unn

had held up her dignity to the day of her death. So they now drank

together Olaf's wedding and Unn's funeral honours, and the last day of

the feast Unn was carried to the howe (burial mound) that was made for

her. She was laid in a ship in the cairn, and much treasure with

her, and after that the cairn was closed up (Laxdaela Saga, Ch.7).

Furthermore, the ship burial discovered in 1904 at Oseberg (fig.5) revealed

itself as the grave of a noble woman of sufficient status to warrant a

very lavish burial. Apart from the boat, the grave also

contained an assortment of artifacts including three sledges, a cart, a

saddle and the remains of ten horses and two oxen, tents, beds and

other domestic items that the Lady would need in her next life. The

ship was most likely used as coastal transportation by the noblewoman,

rather than a working ship or “modern” warship, but still embodies

transitional features found in later ships.

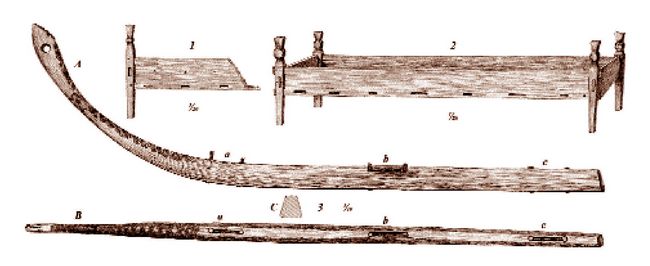

Fig.6: Oak artifacts from the Gokstad ship: (top) bedsteads; (middle and below) sledge runners (Nicolaysen, 1882, Plate VII).

Similarly to that found at Sutton Hoo, the Gokstad ship appears to have

been the burial vessel of a king - undoubtedly Ólav Gierstaða-Alf, and

this is recorded in the Yngling Saga (Illsley 1999). This record, the

first chapter of the Heimskringla, details the Yngling dynasty of

Sweden, allegedly descended from the fertility god/king Yngvi-Frey

(Magnusson 1980). The saga states that Ólav died of an infection in the

foot and is buried at Geirstadir, of which Gjekstad (Gokstad) is a

corruption (Brøgger, Shetelig 1971). An anatomical examination of the

skeleton from Gokstad (fig.8) indicated that it was a well-muscled man

in his late fifties who had suffered greatly from arthritis in the left

knee and ankle (Magnusson, 1980). At the time the ship was interred,

around AD 880, Ólav would have been near sixty years old; thus if the

date and medical evidence are correct, it remains consistent with the

theory that Gokstad indeed housed the remains of Ólav Gierstaða-Alf.

The chieftain was laid out in his best clothes, and placed in his boat

with all that he would need for his long journey, including three

smaller boats (Brøgger, Shetelig, 1971). In addition, many

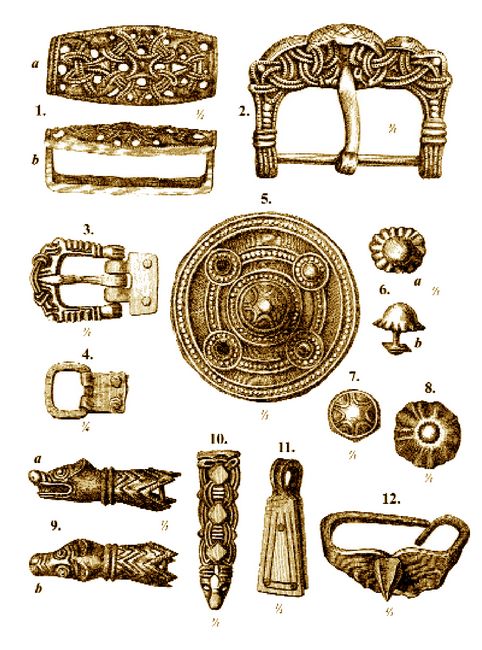

domestic utensils were recovered, a game board, a carved sleigh (fig.6), wooden

spades, and several smaller items, such as gold thread, pieces of dark

cloth, remains of a leather purse, iron belt buckles and some gilded

bronze and lead ornaments (fig.7) (Brøgger, Shetelig, 1971). The mound,

unfortunately, had been pilfered at some point in time, and the thieves

had made a large hole in both the burial chamber and the side of the

ship. We can only imagine the grandeur of the items that the ship had

originally carried. The chieftain was laid out in his best clothes, and placed in his boat

with all that he would need for his long journey, including three

smaller boats (Brøgger, Shetelig, 1971). In addition, many

domestic utensils were recovered, a game board, a carved sleigh (fig.6), wooden

spades, and several smaller items, such as gold thread, pieces of dark

cloth, remains of a leather purse, iron belt buckles and some gilded

bronze and lead ornaments (fig.7) (Brøgger, Shetelig, 1971). The mound,

unfortunately, had been pilfered at some point in time, and the thieves

had made a large hole in both the burial chamber and the side of the

ship. We can only imagine the grandeur of the items that the ship had

originally carried.

Fig.7: Viking metal artifacts from the late

9th century Gokstad ship, including strap slide (1); bronze buckles

(2-4); lead strap mounting (5); bronze studs (6-8); silver pendant (9);

bronze strap mountings (10,11); and iron horse hoof mounting (12)

(Nicolaysen, 1882, Plate X).

While ships such

as Gokstad and Nydam were submerged in chambers, they were not

necessarily marked in any other way. Several burial sites exist,

however, marked with stone outlines of a ship - although there is no

vessel below the surface. The outlines are merely symbols for the

person buried there - a virtual ship. At Lindholm Høje, Denmark, site

of one of the greatest Viking burial grounds in Scandinavia, most

graves contained cremations and dated from AD 500 onwards. Many of

these sites had also been marked out with stone, in patterns either

triangular, rectangular, round or oval.

By the beginning of the Viking period in the ninth century AD,

these stone configurations became boat-shaped. Most of them were about

eight meters in length, but there is one of a whopping 23 meters

(Magnusson, 1980). This practice of outlining graves was not new to

Scandinavia, but the shapes at Lindholm Høje represent a revival in

interest of the ship in Scandinavian society - boats were no longer

viewed only as a means of transportation in this world, but led to the

continuing symbolic voyage after death. By the beginning of the Viking period in the ninth century AD,

these stone configurations became boat-shaped. Most of them were about

eight meters in length, but there is one of a whopping 23 meters

(Magnusson, 1980). This practice of outlining graves was not new to

Scandinavia, but the shapes at Lindholm Høje represent a revival in

interest of the ship in Scandinavian society - boats were no longer

viewed only as a means of transportation in this world, but led to the

continuing symbolic voyage after death.

Fig.8:

Burial in Gokstad ship from original site report. Rough spots on femur

at left indicate severe arthritis (Nicolaysen, 1882, Plate XII).

Another

burial complex of this sort from Sweden is known as “Anund's Mound” or

Anundshög. At this enormous site, the king would have once met his

people and exchanged mutual oaths of allegiance. Beside the mound there

are fifteen standing-stones, discovered in the 1960s and re-erected to

their original upright positions. The site has been associated with

King Braut-Önund, who appears in Snorri Sturluson's Ynglinga Saga.

Snorri relates that he was the most popular of kings, which would

explain his association with the huge mound. The date of the Anundshög

is still debated, however, and may be as old as the Bronze Age. Another

stone ship-setting is visible on the Isle of Man at Balladoole, sitting

on the edge of an Iron Age hillfort (Magnusson, 1980).

Through the evidence found at ship-burial sites, and other grave

locations, it is clear that there was a common belief among the Norse

peoples in life after death - a continuing of existence in which death

was only one chapter among many (Brent, 1975). It is also demonstrated

that there was not only a continuing of life, but of social status -

the most complex funerals were those of the most wealthy and powerful

men, and this evidence comes not only from grave goods but from

accounts such as those found in sagas and epics.

The introduction of Christianity to the northern realms of western

Europe did not eliminate the Viking way of life in its entirety.

It obviously quelled the more pagan practices, yet it is remarkable

that saga literature, taken as a whole, did remain relatively

unaffected by Christian norms. One may be tempted to suspect this was

the result of an exceptionally faithful and tenacious tradition from

the saga age. Vikings have always been portrayed as stubborn,

determined and vigorous people - that their earlier ways of life should

have survived the onset of Christianity it not surprising.

.

References: . Arent, Peter. 1975. The Viking Saga. London, Weidenfield & Nicholson.

Brøgger, A.W., and Haakon Shetelig. 1971. The Viking Ships. London, C. Hurst & Co.

Brøndsted, Johannes. 1960. The Vikings. (trans. Kalle Skov). London, Penguin Books.

Encomium Emmae Reginae. Orig. 11th c. AD (ed. A. Campbell, 1949). London, Royal Historical Society.

Eyrbyggja Saga. Orig. 13th c. AD (trans. Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards, 1989). London, Penguin.

Hallberg, Peter. 1962 The Icelandic Sagas. (trans. Paul Schach). University of Nebraska Press.

Icelandic Sagas 1999. www.south.is/sagas.html

Illsley, J.S. 1999. History and Archeology of the Ship - Lecture Notes. www.history.bangor.ac.uk/shipspecial/

Kirkby, Michael Hasloch. 1977. The Vikings. Oxford, Phaidon Press.

Ladby Ship Museum, 1999. The Ladby Ship. www.vikinger.dk/english/ladby.html

Laxdaela Saga Orig. 13th c. AD (trans. Murial Press). http://sunsite.berkely.edu/ OMACL/Laxdaela/

Magnusson, Magnus. 1980. Vikings! London, The Bodley Head.

Medieval Scandinavia. Revised 1999. http://home. ringnett.no/bjornstad/vikings/ introduction.html

Ministry Foreign Affairs. Danish Vikings. www. um. dk/english/danmark/ om_danmark/ vikings.ship.html

Page, R.I. 1995. Chronicles of the Vikings. Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

Sawyer, P.H. 1971. The Age of the Vikings. London, Edward Arnold (Publishers) Ltd.

Schach, Paul. 1984. Icelandic Sagas. Boston, Twayne.

Sturluson,

Snorri. orig. 13th c. AD. Heimskringla (From the Sagas of the Norse

Kings). (trans. Erling Monsen, 1967). Oslo, Dreyers Forlag.

Sturluson, Snorri. orig. 13th c. AD. Prose Edda. (trans. Jean I. Young, 1954). Cambridge, Bowes & Bowes.

“Viking Burials on the Isle of Man.” 1999. www.anglia.co.uk/angmulti/vikings/ iom/burials.html

.

This article appears in Vol.2, No.3 of Athena

Review.

.

|

|