| Athena Review, Vol. 2, No. 3 (2000) | | |

Viking York

| | | | |

|

by Brenda Ralph Lewis . Of

all the Viking centers established in the British Isles between the 8th

and 11th centuries AD, York is historically the best known. During the

centuries before the Vikings captured the city in AD 866,York had

substantial ancient Roman and Anglo-Saxon precedents. This set it apart

from other Viking centers in the British Isles including Dublin, a

newly-founded, contemporary town whose rulers spawned frequent

rivalries and attempted takeovers of York.

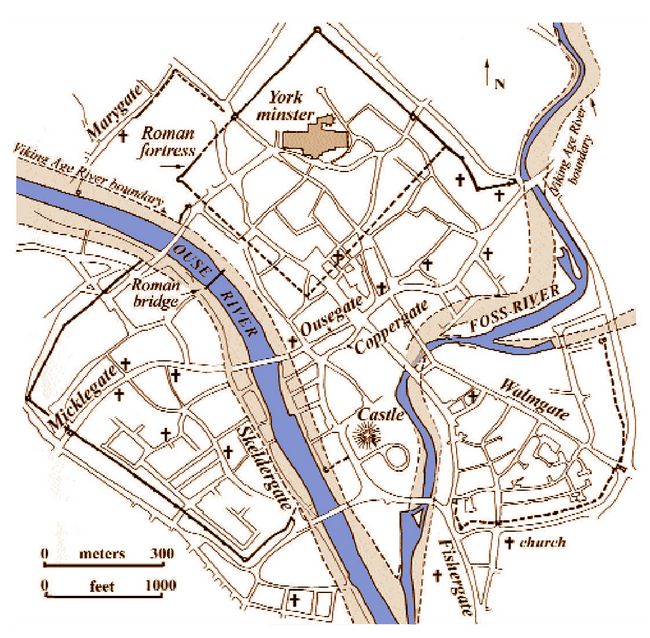

As

a result of an ongoing study of British Viking settlements by

archaeologists, York (fig.1) has provided a treasure of details from

the relatively little-known 9th and 10th centuries. It is also a unique

example of long-term urban continuity.

Called Eberacum

by the Romans who in AD 78 turned the town into one of three legionary

headquarters in Britain, York was second only to London (Londinium)

as an important military and administrative post, and remained so until

the end of Roman rule almost 350 years later. The emperor Septimius

Severus died in York in AD 211, and the city was also the scene, in AD

306, of the death of Emperor Constantinus I Chlorus and the

proclamation of Chlorus’ son, Constantine the Great as his successor.

Substantial remains of 4th century AD Roman administrative buildings

may be seen today underlying York Cathedral (see AR 1,1 and 1,2).

In

about AD 400, shortly before the Romans finally abandoned Britain, the

Anglo-Saxons, after raiding eastern England for 200 years, seized

control of York and turned it into a major royal, ecclesiastical, and trading center named Eoforwic. Anglo-Saxon York lasted 4 50 years, and during that time, the English scholar Alcuin (AD 735-804), advisor to Charlemagne, made it a center of learning famous throughout the Christian world. In this period of AD 400-850, early stages of the church and monastery later to became Yorkminster or the cathedral were built over the old Roman legionary fortress (fig. 1). 50 years, and during that time, the English scholar Alcuin (AD 735-804), advisor to Charlemagne, made it a center of learning famous throughout the Christian world. In this period of AD 400-850, early stages of the church and monastery later to became Yorkminster or the cathedral were built over the old Roman legionary fortress (fig. 1).

Fig.1: Plan of Viking York, showing earlier Roman features (after Hall 1988, Ordnance Survey 1988, and Richards 1991).

York

thus had a long-term urban history prior to the unsettled times of the

early 9th century AD, when Vikings from Scandanavia established a

foothold in Ireland at a new settlement they called Dyflin

(later Dublin), initially as base for piracy (ca. AD 840), afterwards

as a town (AD 917). In AD 865 the Vikings reached Northumbria and

marched on York at what happened to be a fortunate time (for them). The

Anglo-Saxon Northumbrians were engaged in civil war, having overthrown

one king, Osbert, and given allegiance to another, Aelle. With

Northumbria in political disarray, it was comparatively easy for the

Vikings, led by Ivarr the Boneless, King of Dyflin, to overrun the city

on 1 November 866. Too late, the Northumbrians joined forces, but their

assault in AD 867 was a failure and both their rival kings were killed.

Falling

into the hands of the Vikings was the worst nightmare of the time. The

first of many terrifying facts about them was their ability to cross

the North Sea to reach England - a feat never achieved or thought

possible before, but easily within the superb seafaring skills of the

Vikings. They first appeared off the east coast of England on June 1 of

AD 793, when they sacked the monastery on Lindisfarne, two miles off

the coast. Returning again and again, they burned and pillaged and

despoiled churches and villages alike before carrying off as slaves

those they did not kill. For a time, the Vikings took the ransom,

called Danegeld (Dane’s gold), which was paid them to go away. Before

long, though, environmental and other pressures meant that the Vikings

came not simply to raid, but to stay.

Scandinavia

was harsh, barely fertile and overcrowded, making richer territories

elsewhere in Europe an attractive target. This was why the ‘great

heathen force’ of Vikings which arrived in Northumbria in AD 865 and

seized York the following year were intent on conquest and settlement.

The Anglo-Saxons were unable to stand up against such formidable

warriors, and ultimately, the Vikings devastated Northumbria before

moving on to fresh conquests.

Their

most dazzling single prize, however, was York, whose successive Roman

and Anglo-Saxon occupations as a military, ecclesiastical, and trading

center provided the Vikings with a number of ready-made urban features

(fig.1). These began with the massive Roman-built fortress walls, over

3m high, remaining solid enough after four centuries for the Vikings to

use them as part of the defences for their own York, or Jorvik, as they

named it. The more remote Dyflin, by contrast, was defended only by

earth fortifications along its perimeter.

Jorvik’s

location and long-term settlement resources allowed the transplanted

Vikings to develop from raiders to merchants. In the 87 acres (36 ha)

enclosed within the walls of Jorvik, they developed a city that would

become a prime commercial, trading and residential center and the

capital of their Kingdom of York. The streets possibly had metalled

surfaces, and the Vikings also created a major crossing over the River

Ouse, with a main street, Micklegate, “the great street,” leading to it, whose crossing remains in place to this day (fig.1).

The

layout of Jorvik set a standard of street planning and domestic

building which later appeared across the Irish Channel in Dyflin. Both

Jorvik and Dyflin had irregular street plans, partly prompted in each

case by the local geography. Other comparisons, however, suggest a

common cultural tradition which contrasted markedly with the old Roman

grid plan.

The areas excavated by the York Archaeological Trust after 1976 were at 16-22 Coppergate, 58-59 Skeldergate, 6-8 Pavement, the space between 25-27  High Ousegate

and 5-7 Coppergate, and stretches of Walmgate. From the wealth of finds

made at these sites, currently on exhibit at the Jorvik (Viking York)

Centre in Coppergate, York, Jorvik has revealed a series of building plots complete with backyard wells and cesspits. High Ousegate

and 5-7 Coppergate, and stretches of Walmgate. From the wealth of finds

made at these sites, currently on exhibit at the Jorvik (Viking York)

Centre in Coppergate, York, Jorvik has revealed a series of building plots complete with backyard wells and cesspits.

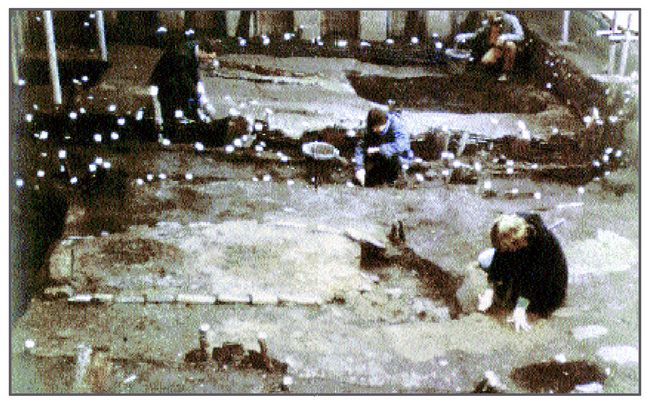

Fig.2: 10th century wattle and post buildings (AD 900-950) excavated (York Archaeological Trust).

Houses

were of the post-and-wattle type (fig.2) , so-called because their main

wall post or roof supports were interwoven horizontally with wattlework

rods of hazel, willow or oak. Built about AD 930-935, Coppergate street

had long narrow lots aligned to wattle fences between the street and

the Foss River (fig.3). Wattlework panels were also laid down outside

to make narrow pathways. Similar patterns occurred in Dyflin, where the

intersecting roads joined the principal street and extended back

towards the River Liffey.

House

construction in Jorvik was rather more standardised than it was in

Dyflin. The plots were a regular 18 ft or so in width, suggesting,

perhaps, that official rules were

laid down in such matters, and also, perhaps, long-term continuity of

ownership. Within these plots, rectangular houses with earth floors

were built measuring 14.5 ft wide by about 27 ft in length. In Dyflin,

individual houses varied greatly in size and position, with the only

consistent feature apparently that the main axis of a house paralleled

the length of the plot. House sizes there measured an average 28 by

15.6 ft in size, slightly larger than in Jorvik.

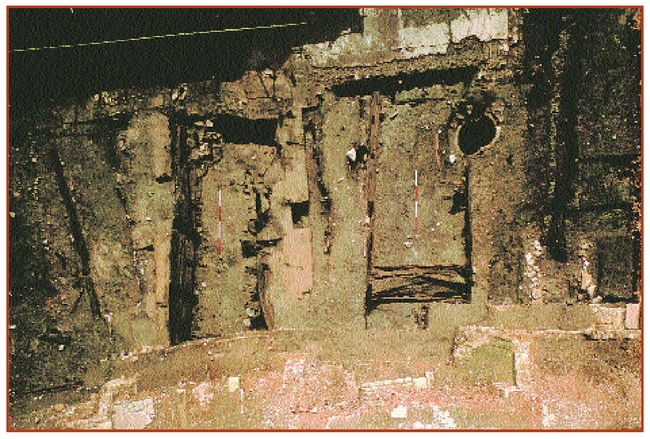

Fig.3: Aerial view of

four adjacent sunken buildings with plank walls including a workshop,

late 10th century AD, Coppergate excavation. The round brick well at

right is a later intrusion (York Archaeological Trust).

Along

the walls in some Jorvik houses were wattle-lined, soil-filled benches

whose seats were covered with soft plants, and in the center, a clay

hearth measuring about 6 by 4 ft lined in stone. In some houses, its

central position was indicated by the traces of ash and areas burned

red. Others, though, have been found surrounded by old Roman tiles or

limestone rubble. The wood and thatch structure of houses inevitably

made the hearth a fire hazard, but a presumed lack of windows meant

that it also served as a principle source of indoor lighting.

Supplementary lighting probably came from stone or pottery lamps with

wicks which burned oil or fat.

The earlier Viking houses in Jorvik had only one storey (the wattlework walls were

not strong enough for an upper floor), and there was probably a

thatched roof whose weight was supported by the more substantial

uprights. However, four houses excavated at Coppergate and dating from

the late 10th century (fig.3) revealed an extra storey underground.

This new feature consisted of a basement at a depth of about 6 ft (1.8

m), approached by a stone-lined corridor and furnished with strong oak

beams, posts and planks. Excavations in Dyflin have shown that similar

buildings were constructed there, though at a rather later date.

A

particularly fortunate feature also shared by Jorvik and Dyflin was a

damp environment which favoured the preservation of ancient remains.

Jorvik, lying beneath the layers built up by time, survived well in the

oxygen-free, organic-rich soils which protected organic materials such

as wood, leather and cloth from the b acteria-caused decay. Even insects and other animal remains, seeds, pollen, fruit-pips, twigs, plants, thatch, wood chips, straw, heather, and mollusks were found more or less intact across the centuries. Jorvik is therefore an archaeological gold

mine virtually unique in the detail it can offer, and the Ancient

Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act (1979) which recognised the

center of York as Area of Archaeological Importance, has enabled that

detail to be revealed. acteria-caused decay. Even insects and other animal remains, seeds, pollen, fruit-pips, twigs, plants, thatch, wood chips, straw, heather, and mollusks were found more or less intact across the centuries. Jorvik is therefore an archaeological gold

mine virtually unique in the detail it can offer, and the Ancient

Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act (1979) which recognised the

center of York as Area of Archaeological Importance, has enabled that

detail to be revealed.

Fig.4: Disk brooches from Viking York, cast of silver (top left) and lead alloy (York Archaeological Trust).

Together

with more durable relics of stone, metal (fig.4), bone and pottery,

these discoveries have made it possible to build up a detailed picture

of the way life was lived in Jorvik. The Jorvik Centre’s proud, and

justified, boast is that there is sound archaeological evidence for

their pictorial reconstructions and tableaux right down to the lichen

the Vikings used to dye cloth and the precise weave of the clothes and

socks they wore. One of the most complete and rare finds at

Jorvik was a 10th century sock, knitted from wool on a single needle or

nålebinding.

In addition, skulls retrieved from the cemetery near the site where the

Viking Age cathedral is presumed to have stood, have been used at the

Jorvik Centre to recreate the facial appearance of the town’s

inhabitants, courtesy of modern high-tech laser-scan technology.

Since

the houses were used as both living quarters and workshops, the same

sites have served to build up a picture of working as well

as domestic life. Quern-stones with which the Vikings ground corn to

make flour have been found, together with ancient cereal grains. Other,

microscopic, evidence requiring careful analysis, indicates the Viking

diet included bran, herbs, vegetables,

fruits and eggs; whose seeds, pips and eggshells have been found. These

went with the usual fish and meat, which included goose, something of a

delicacy. Further

proofs of the food the Vikings ate comes from analysis of the

coprolites they left behind in their privies, found in yards behind the

houses. The inhabitants of Jorvik were prone to intestinal parasites,

an inevitable outcome when drinking water in the wells, pits used to

dispose of waste, and the quartering of animals, with their litter and manure, all existed in close proximity.

A considerable number of tools have been excavated in houses at Jorvik. Among many other implements, there was a fine set of woodworking tools (including a drawknife,

chisel axehead, and auger), as well as sickles, sharpening stones and

knives. Jewelry moulds, the cores of wooden bowls, scraps of cloth,

offcuts of leather, bucket staves - all this provides a picture of a

busy community, and a sk ilful one. Baked clay loom weights indicated the production of textiles. Combs, pins and whorls for spindles were made by bone- and antler-workers. Blacksmiths used tin, or lead and copper alloys to plate iron, and also worked in gold and silver (fig.4). ilful one. Baked clay loom weights indicated the production of textiles. Combs, pins and whorls for spindles were made by bone- and antler-workers. Blacksmiths used tin, or lead and copper alloys to plate iron, and also worked in gold and silver (fig.4).

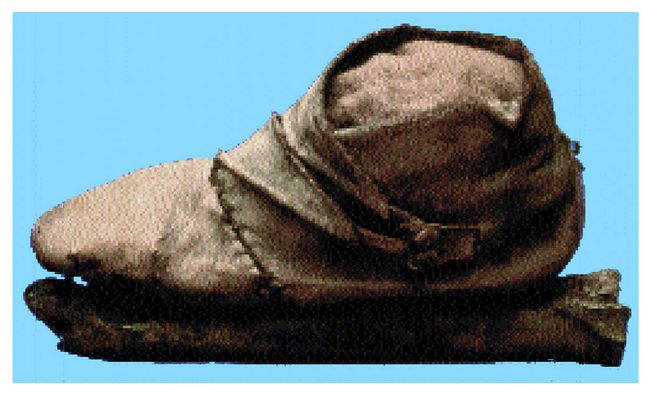

Fig.5: Leather boot with bone skate (York Archaeological Trust).

Elsewhere,

pieces of leather waste and the discovery of a wooden last indicate the

making and repairing of shoes, together with belts and scabbards, many

of which were ornately decorated. Leather boots with bone skates have

been found (fig.5), and traces of wool and bits of fleece have

evidenced wool processing and fleece imports. Scraps of

jewelry showed that decorative pins and brooches were made in Jorvik together with many items mass-produced for quick, cheap sale. These included buckles and brooches

made of lead (fig.4), gold earrings, glass beads decorated with gold

leaf, necklaces of jet and glass beads and cooper alloy and bone pins

as clasps for clothing. More prosaically, iron was used in the manufacture of cooking pots, frying pans, padlocks and keys and wood for bowls and spoons.

Amber imported from Scandinavia or the Baltic went to make pendants and rings (fig.6), and several other exotic goods and materials arrived along the River Ouse to

be landed at the port of Jorvik. The remains suggest a very

wide-ranging network of trading contacts, not only to the ancestral

homelands in Scandinavia and the rich trading

port of Dyflin, but as far afield as the Mediterranean, the Middle

East, the Indian Ocean, Asian Russia, the Byzantine Empire and the Far

East.

Fig.6: Amber beads from Coppergate Street in York (York Archaeological Trust)

A

considerable amount of silk, in 23 fragments, has been found at 16-22

Coppergate suggesting extended trade routes which ran from China, the

original site of silk manufacture (fig.7). Other indications were an

Islamic coin from Samarkand (Uzbekistan), notable even though it proved

to be a 10th century forgery. Cargoes of wine and quernstones made of

lava, whetstones, pottery, soapstone cooking vessels, furs and

dyestuffs came into Jorvik from Scandinavia and northern Europe,

including Pingsdorf pottery from the German Rhineland.

Jorvik

also took in goods and materials from the area immediately surrounding

the town. There were several villages, some Anglo-Saxon foundations,

some Viking, in cl ose

proximity to Jorvik and one of them, Copmanthorpe, to the south,

revealed its nature in its name, “outlying farmstead or hamlet

belonging to the merchants.” It is likely that

the merchants of Copmanthorpe and other riverside villages were

the first to receive goods from the trading vessels sailing up

the River Ouse and afterwards took them to Jorvik for sale in the

markets. ose

proximity to Jorvik and one of them, Copmanthorpe, to the south,

revealed its nature in its name, “outlying farmstead or hamlet

belonging to the merchants.” It is likely that

the merchants of Copmanthorpe and other riverside villages were

the first to receive goods from the trading vessels sailing up

the River Ouse and afterwards took them to Jorvik for sale in the

markets.

Fig.7: Silk reliquary pouch with embroidered cross (York Archaeological Trust).

Local

manufactures as well as imports were on sale. Industry in Jorvik was

well enough established for individual streets to be identified with

certain trades. Coppergate was the center of carpentry, as Skeldergate

was the street of the shield-makers, and among them were the makers of

decorative metalwork as well as a glass bead-making industry. Blue soda

glass and high-lead green or black glass were used in the manufacture

of beads. The soda glass was most probably gleaned from small

quantities of scrap left behind in Roman times. Melted down on rough

ceramic disks, it appears to have been scraped off, then formed into

beads. High-lead glass has been less conclusively traced, but it may

have been used as a form of iron, to smooth off linen.

Social

as well as domestic and working life has also been reflected in the

Jorvik finds which reveal the entertainments that occupied the Vikings’

spare time, apart from the traditional recital of the great sagas, with

their brave warriors and mighty deeds and the glory that accrued

through earning an honoured place in Valhalla. The

Vikings had a game called hnefatafl, played with pieces of bone and

stone which were among the finds at Jorvik. Dice made of bone and

gaming counters in profusion have also been uncovered. Among Viking

musical instruments, there was a set of boxwood pan pipes, a flute made

from the leg-bone of a swan and a tuning peg decorated with animal

heads for some instrument yet to be excavated but possibly gone

forever.

The

excavation of Jorvik has cast light, too, on Viking religious beliefs

which appear to have been mixed between the Christianity they adopted

when they came to Britain and their own ancestral pagan creed. Although

numerous churches were built at Jorvik, Viking pagan beliefs died hard

and persisted for a century or more after their arrival from

Scandinavia. This is illustrated by a die, dated about AD 920-927, used

for minting St. Peter’s Pence, a tax paid to the papacy in Rome. The

die showed both the symbol of the Cross and, on the other side, the

hammer of T hor, the Viking god of thunder (cf. fig.8). Similarly,

a coin of Olaf Guthfrithsson, King of York from AD 939 to 941, carried

a bird emblem, possibly the raven which was a symbol of Odin, principal

god of the Norse pantheon; the coin was inscribed not in the customary

Latin, but in Old Norse. In addition, Jorvik excavations have unearthed

a 10th century stone grave marker, probably originating at All Saints’

Church nearby, with an interlaced animal design more typical of pagan

than of early Christian practice. hor, the Viking god of thunder (cf. fig.8). Similarly,

a coin of Olaf Guthfrithsson, King of York from AD 939 to 941, carried

a bird emblem, possibly the raven which was a symbol of Odin, principal

god of the Norse pantheon; the coin was inscribed not in the customary

Latin, but in Old Norse. In addition, Jorvik excavations have unearthed

a 10th century stone grave marker, probably originating at All Saints’

Church nearby, with an interlaced animal design more typical of pagan

than of early Christian practice.

Fig.8: Silver penny from

St. Peter Coinage under the Danish kings of York (AD 905-910). The

obverse (shown) reads SCI PETRI M, with images of a sword and a

downturned hammer for Thor. The reverse has a Christian cross and names

York as EBORACE CIV (CNG 1998).

As

Jorvik, York had a surprisingly short life. Control of the city was

continually disputed with the Anglo-Saxons, who finally prevailed,

after some ninety years, when the last Viking leader, the

flamboyantly-named Eric Bloodaxe, was driven out in AD 954. Bloodaxe,

who had a gory reputation as a fratricide seven times over, was more

typical of the Vikings in their earlier, marauding guise. However, the

great value of the excavations in York has been to show another,

less familiar image of the Vikings as civic organisers, planners,

architects, roadmakers, artisans, artists, traders and just ordinary

people, leading ordinary lives.

References: . Addyman, P.V. (editor) The Archaeology of York. Series of reports by the York Archaeological Trust.

Hall, Richard A. 1984. The Viking Dig (first discoveries at Coppergate, York excavations). London, Batsford.

Hall, Richard A. 1994. Viking Age York. London, Batsford, for English Heritage.

Hall, Richard A. 1995. Viking Age Archaeology in Britain and Ireland. Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire, Shire Archaeology, Shire Publications.

Ordnance Survey. 1988. Historical Map & Guide: Viking & Medieval York.

Richards, Julian D. 1991. Viking Age England. London, Batsford, for English Heritage.

.

This article appears in Vol.2, No.3 of Athena

Review.

.

|

|

| Athena

Review Image Archive™ Main

index of Athena Review

Copyright © 2000-2019 Athena Publications, Inc.

(All Rights Reserved). | | |

.

|