|

James Allan Evans Professor Emeritus, University of British Columbia, Vancouver

.

Imperial favor had made Constantinople into a city greater than its nearest

rival in the Mediterranean world, Alexandria. The site which Constantine

had chosen for his “New Rome” was not ideal. It was arid and prone

to earthquakes. No olive trees could flourish there. It was fed by grain

shipped from Alexandria, diverted from supplies intended for Italy, and Italy

was left to support itself with grain shipments from Sicily and North Africa.

But the cargo ships that sailed from Alexandria to Constantinople encountered

head winds and contrary currents in the Hellespont which could make it impossible

to approach the wharfs. The Emperor Justinian (527-565) built granaries at

the entrance to the Hellespont on the island of Tenedos to store the grain

brought from Egypt until there was a favorable wind, but that meant that

stevedores at Tenedos had to unload the grain sacks, store them until the

weather changed, and then reload them. It was back-breaking work, and must

have provided illicit feasts for rats and other rodents. Yet Constantinople

grew into a splendid city of about half a million persons in Late Antiquity,

at a time when Paris, Milan, and Ravenna were large villages and Rome was

a decaying museum-without-walls.

In the southeast corner of the city was the Great Palace. Like the Kremlin

in Moscow, it was not a single building, but rather a group of them surrounded

by a wall and entered by a magnificent gateway. Opposite the palace, across

a square called the Augustaeum, was the cathedral church, Hagia Sophia, and

to the west of the palace was the Hippodrome and the Baths of Zeuxippus.

The Hippodrome is in ruins now, but on the seaward side we can still see

some of its massive substructures and in what remains of the arena we may

view some of the monuments that once adorned the spina, including a bronze

serpent column taken from Delphi, where Pausanias, the Spartan who led the

Greeks to victory over the Persians at Plataea in 479 BC, had dedicated it

as an offering to Apollo. The main street of Istanbul, the Divanyolu, is

the main street of Constantine’s city, the Mese. It runs past the “Burnt Column,” all that remains of a pillar which once held a

bronze figure of Constantine which was a recycled statue of Apollo, and marked

the “Oval Forum” where there stood the bronze Athena Promachos

statue by Pheidias which had once looked over ancient Athens from the Acropolis.

Constantine had adorned his city with works of art taken from various sites

in Greece, and his successors, down to the 6th century, followed his example.

Beyond the Oval Forum, the Mese continued west and one of its branches led

to the Golden Gate which pierced the great Theodosian walls that were never

broken until the Turks attacked in 1453. in Greece, and his successors, down to the 6th century, followed his example.

Beyond the Oval Forum, the Mese continued west and one of its branches led

to the Golden Gate which pierced the great Theodosian walls that were never

broken until the Turks attacked in 1453.

Fig.1: Roman aqueduct in Istanbul, dating from the 3-4th c AD (photo: Athena Review). It was a busy, disorderly city, full of life and at a time when older cities

of the empire were shrinking, it continued to grow. The porticoes lining

either side of the Mese were full of merchants’ stalls. Nearest the

imperial palace were the perfumers, for the scent from their shops was considered

suitable for the sacred persons of the emperor and empress. Further along

the Mese were silversmiths and money-changers and the Oval Forum of Constantine

was a center of the fur trade. Near the Baths of Zeuxippus stood the “House

of Lamps,” so-called because its windows were lamp-lit at night, and

there the finest dyed silks were on display. The rich lived in palaces, and

the poor eked out an existence on the streets. The numerous churches advertised

the piety of the wealthy class, but the poor supplied the mob which was forever

restless and easily ignited by religious disputes.

Second only to theology and its controversies, the crowd loved chariot-racing.

In the Hippodrome, four chariot factions competed, marked by their colors,

Red, White, Blue, and Green. Their fans sat in designated sections in the

Hippodrome while the emperor had a loge on its east side, next to the imperial

palace. The crowd did not always come to the Hippodrome merely to cheer the

charioteers. This was also a place where it could voice discontents and shout

complaints, and the emperor, using a herald with a trained voice, could reply.

There was a rough-and-ready democracy here, where emperors encountered public

opinion, and revolutions might be born.

In 491, the Emperor Zeno the Isaurian died. He had left a brother who expected

to succeed to the throne, but Ariadne, Zeno’s widow, married an elderly

bureaucrat, Anastasius. The Isaurians whom Zeno had

favored were outraged, but Anastasius banished Zeno’s brother to upper

Egypt where he died of starvation and by 497, he had quelled the Isaurians

in the capital and put paid to notions of independence in Isauria itself.

The patriarch was also unhappy at Ariadne’s choice, for Anastasius was

a known Monophysite sympathiser, and as part of the coronation ceremony,

the patriarch insisted that he take a coronation oath to uphold orthodoxy.

But Anastasius was an able administrator, though once the Constantinople

mob almost dethroned him when he introduced an addition to the liturgy in

Hagia Sophia that smacked of Monophysitism. He was forced to appear in the

Hippodrome, repentant, bareheaded without his crown, when mob sentiment turned

to pity and he survived. But his attempts to negotiate a solution to the

schism with Rome came to nothing. Rome would accept nothing less than the

Chalcedonian Creed and unless Anastasius surrendered, the pope would not

lift the excommunication.

Then in 518, Anastasius died suddenly and left a vacuum of power. His obvious

heir was his nephew, a thorough mediocrity, but he was in Antioch commanding

the armed forces in the east. It was up to the Constantinople senate to make

the choice, and the picturesque but powerless body was unused to making decisions

about anything. Yet it met in the palace with the patriarch and the chief

bureaucrats and negotiated, while the people gathered in the Hippodrome and

waited impatiently. With negotiations dragging on, the situation threatened

to get out of hand and a panicked senate opted for Justin, the commander

of the effective palace guard known as the Excubitors. Justin had risen through

the ranks and married a former slave, Lupicina, whom he had purchased as

his mistress. The new emperor was presented to the Hippodrome crowd which

raised the salute: “Justin, may you be victorious!” Lupicina, adopting

the more suitable name of Euphemia, became empress.

Justin also adopted his nephew, Justinian, who later inherited the throne

and provided the expertise that his uncle lacked. But both men agreed that

the schism with Rome must end. That meant surrendering to Rome’s demands,

and Pope Hormisdas was adamant. He demanded that the emperors Zeno and

Anastasius, and the patriarchs who cooperated with them be anathematized.

Monophysitism was to be outlawed and its followers persecuted if they would

not recant. In cooperation, Justin ousted Monophysite bishops and monks from

their sees and monasteries. The patriarch of Antioch, Severus, the leading

Monophysite of the day and Anastasius’ protegé, avoided arrest

by secretly fleeing to Alexandria. Only Egypt remained a safe haven for the

Monophysites, for though the pope urged Justin to extend his persecution

there too, Justin knew how much Constantinople depended on cargoes of grain

from the Nile Valley.

At Amid, modern Diyarbakir in Turkey, monks were driven from their monastery

and nearly died of privation. In their distress they turned to one friend

at court who they knew favored their theology. That was Justinian’s

mistress, an ex-actress named Theodora who had been converted to Monophysitism

in Alexandria, possibly by the patriarch Timothy IV himself. When the monks

banished from Amid appealed to Theodora, she urged Justinian to approach

Justin, and the monks were allowed to go to Egypt and find refuge there.

It was Theodora’s first intervention on behalf of the Monophysites.

In 527, Euphemia (formerly Lupicina) was dead for several years and Justin,

by now senile and suffering from an old wound he had received as a soldier,

appointed Justinian co-emperor and four months later, he died. Justinian

and Theodora became emperor and empress. More than most imperial marriages,

it was a union of equals, for Justinian valued Theodora’s advice, and

Theodora did not hesitate to oppose him when she thought fit, though her

loyalty to her husband was never in doubt. On matters of theology, they agreed

to disagree. But together they presided over the most brilliant period of

early Byzantium, which began with a burst of optimism when it seemed possible

to restore the dominion of the old Roman Empire. Byzantine armies reconquered

Africa, Italy, and part of Spain. But by the end of Justinian’s reign

the mood had darkened. War had depleted the empire’s resources, plague

had cut the population by forty per cent, and the division between the

Monophysites and the Chalcedonian Creed orthodoxy was on the way to becoming

permanent.

Three buildings survive to attest the magnificence of Justinian’s reign.

One is the church of San Vitale in Ravenna. Ravenna, the last refuge of the

emperors of the Western Roman Empire, had become the capital of the Ostrogothic

kingdom of Theodoric, who had made himself master of Italy during Zeno’s

reign in Constantinople. Byzantine forces led by Justinian’s most famous

general, Belisarius, took Ravenna in 540, and the city was to become the

seat of the Byzantine exarch. The construction of San Vitale began while

Ravenna still belonged to the Ostrogoths, and a local banker paid for it,

but it was not dedicated until 547, a year before Theodora died of cancer.

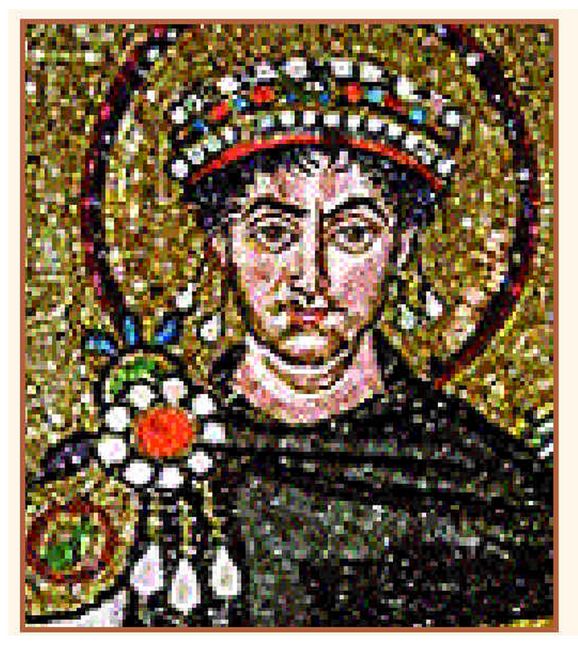

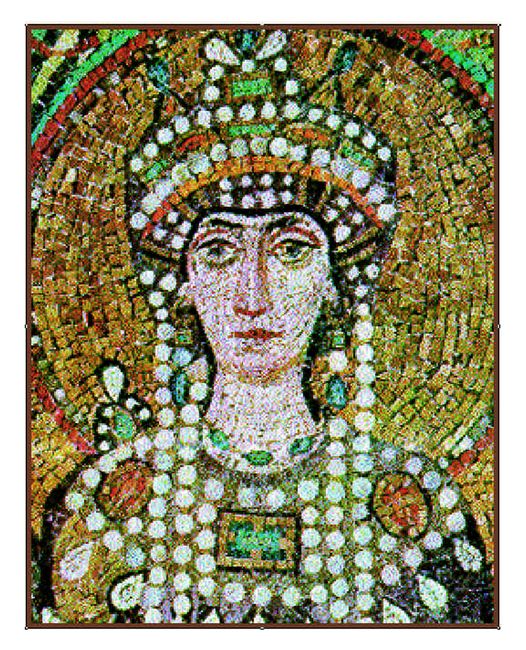

In its chancel, two splendid mosaics face each other on the side walls. One

shows Justinian and his attendants (fig.3). The other shows Theodora surrounded by

her ladies (fig.4). Justinian looks vigorous. Theodora looks severe; the onlooker

can perhaps recognize in her face traces of pain from the cancer which would

soon kill her. Neither Justinian nor Theodora ever came to Ravenna, but this

is where we feel closest to their ghosts. but it was not dedicated until 547, a year before Theodora died of cancer.

In its chancel, two splendid mosaics face each other on the side walls. One

shows Justinian and his attendants (fig.3). The other shows Theodora surrounded by

her ladies (fig.4). Justinian looks vigorous. Theodora looks severe; the onlooker

can perhaps recognize in her face traces of pain from the cancer which would

soon kill her. Neither Justinian nor Theodora ever came to Ravenna, but this

is where we feel closest to their ghosts. Fig.3: Detail of mosaic of Justinian in the Church of St. Vitale in Ravenna, AD 547 (photo: Athena Review).

In Istanbul, the church of SS. Sergius and Bacchus is a twin of San Vitale.

It is now a mosque, and the vibrations of the elevated railway that runs

close by it are slowly cracking the dome. But inside the church on the

entablature under the dome there c an still be seen the inscription hailing

Theodora as “God-crowned whose mind is adorned with piety and whose

constant toil lies in unsparing efforts to sustain the needy.” The church

stood close to the Palace of Hormisdas where Justinian and Theodora lived

while Justin was still alive, and after they moved to the Great Palace, Theodora

filled their former home with Monophysite holy men who flocked to Constantinople

to seek her protection. Saints Sergius and Bacchus was probably their church. an still be seen the inscription hailing

Theodora as “God-crowned whose mind is adorned with piety and whose

constant toil lies in unsparing efforts to sustain the needy.” The church

stood close to the Palace of Hormisdas where Justinian and Theodora lived

while Justin was still alive, and after they moved to the Great Palace, Theodora

filled their former home with Monophysite holy men who flocked to Constantinople

to seek her protection. Saints Sergius and Bacchus was probably their church.

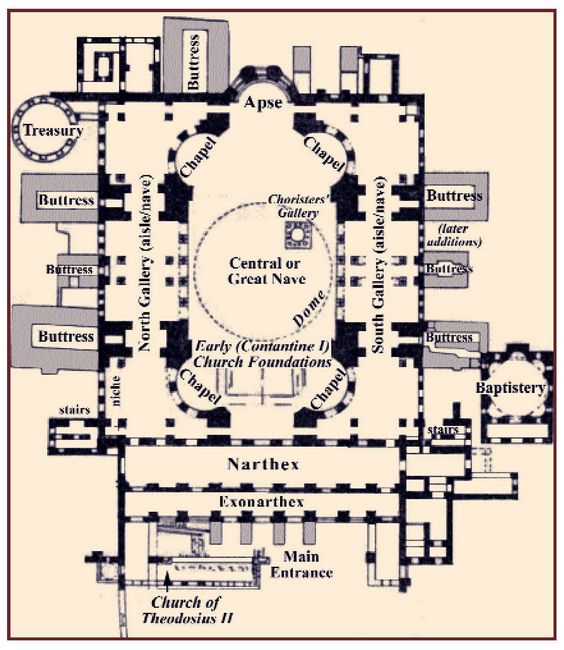

Fig.4: Detail of mosaic of Theodora in the Church of St. Vitale in Ravenna, AD 547 (photo: Athena Review). But the great monument of Justinian’s reign is Hagia Sophia which still

stands intact though it shows the scars of a turbulent history (figs 5-6). Behind it

lies a story. Once he was emperor, Justinian determined to enforce law and

order and to suppress rioting. In January of 532, one group set off a week

of riots and arson that destroyed whole regions of the city and would have

driven Justinian from the throne except that Theodora kept her nerve in the

crisis, and the soldiers that were still loyal cornered the rioters in the

Hippodrome and massacred them. Justinian emerged from the riots stronger

than ever, determined to remake the city and leave his mark on it. The

conflagration destroyed Hagia Sophia, and Justinian was anxious to replace

it with a structure that would glorify his reign.

Hagia Sophia tested the limits of contemporary civil engineering. It is a

great dome placed on a modified basilical church. The first dome that was

built was breathtaking but the outward thrust was too great and the huge

piers that held it up began to tip outwards.

Hagia Sophia tested the limits of contemporary civil engineering. It is a

great dome placed on a modified basilical church. The first dome that was

built was breathtaking but the outward thrust was too great and the huge

piers that held it up began to tip outwards.

Fig.5: Plan of Hagia Sophia. A severe earthquake smote

Constantinople in December of 557, driving the people in terror into the

streets where they shivered in a sleet storm until morning, when the light

revealed a crack in Hagia Sophia’s dome. Stone masons from Isauria set

to work repairing it, but suddenly next year, on 7 May, they had to scramble

for safety as the eastern section came tumbling down. The dome was rebuilt,

making it 7 meters higher, and though there have been later repairs and

reconstructions, this is the dome that still impresses us in modern Istanbul.

Hagia Sophia has served as a mosque and is now a museum, but it still proclaims

the greatness of Justinian’s empire.

Yet the religious schism remained intractable. Once Byzantium overthrew the

Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy and had physical control of Rome, the popes

no longer found it so easy to defy the emperor, and though Justinian continued

to respect the papacy, Theodora regarded the popes as recalcitrant prelates

who should be forced to soften their defense of the Chalcedonian Creed. But

th ough she seconded her husband’s efforts to reconcile the Monophysites

and the Chalcedonians, she cannot have been too sanguine. ough she seconded her husband’s efforts to reconcile the Monophysites

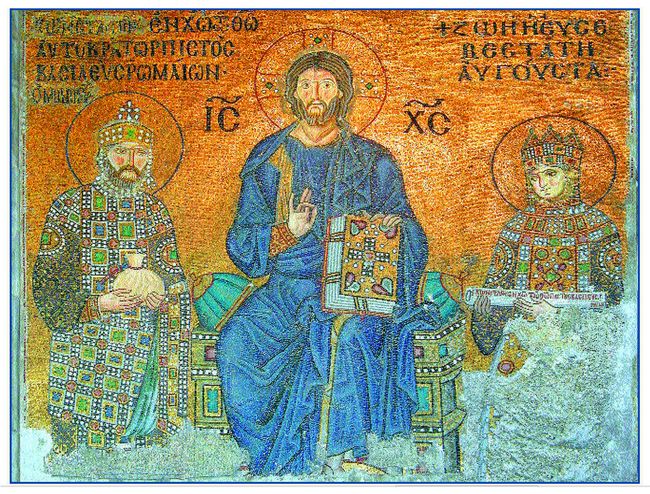

and the Chalcedonians, she cannot have been too sanguine. Fig.6: An 11th century mosaic from Hagia Sophia, showing Christ seated between the Emperor John IX and his wife (photo: Athena Review). In 541, an Arab

client king of the Ghassanid tribe which guarded the south Syrian frontiers

for the empire, asked Theodora for an ordained Monophysite bishop to minister

to his people. Bubonic plague was already killing thousands in Egypt and

was moving into Syria; next year it would reach Constantinople and cut its

population in half. Antioch lay in ruins; the Persians had sacked it in 540,

and were still ravaging the eastern provinces. Whatever private hesitations

Theodora may have had, the imperial government was in no position to refuse

a valuable ally what he wanted. Theodora provided the Ghassanid emir with

two bishops, and unwittingly she became the godmother of a separate Monophysite

church with its own hierarchy. Thereafter the quest to reunite Christendom

with one statement of faith was to grow increasingly futile.

This article appears on pp.16-25 in Vol.3, No.1 of Athena

Review.

.

|

|