Athena Review Image Archive ™

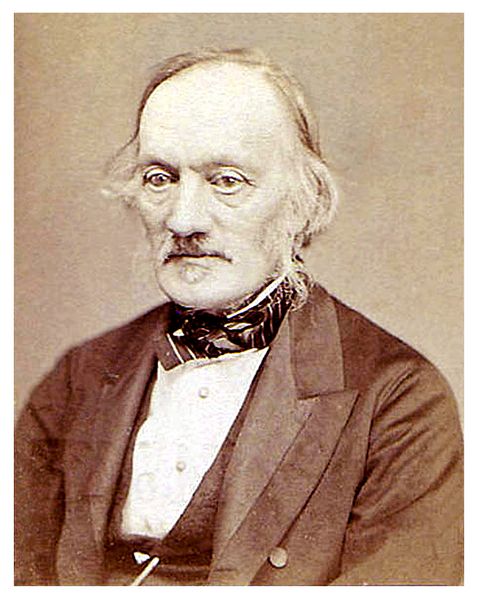

Richard Owen (1804-1892)

Portrait of Richard Owen at about age 60 (photo: ca. 1864)

Richard Owen (1804-1892) was an accomplished and influential British paleontologist. He studied medicine and specialized in comparative anatomy. He was the first to classify large Mesozoic land reptiles as Dinosauria, or "Terrible lizards" (1842). Two members of the initial dinosaur grouping were Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus, both discovered by the geologist Gideon Mantell. Owen (1842), in a move not entirely to his credit, cited himself and Georges Cuvier as the discoverers of the Iguanodon, excluding any credit for Mantell.

Based on fossil remains of hoofed mammals or ungulates, Owen in 1848 was the first to identify the two main groups of odd-toed (Perissodactyla) and even-toed (Artiodactyla) ungulates. Owen recognized and named several large ungulate taxa from South America, including the rhino-like Megatherium from the Oligocene, 32-20 mya (1860).

Based on specimens from the Karoo Basin in South Africa, Owen was also the first to recognize and describe one of the major branches of the Therapsids or mammal-like reptiles, the Anomodontia ("undefined teeth"). In 1845, he described Dicynodon ("two dog teeth"), a major taxon of the Anomodontia, and the type species for the Dicynodonts, one of two branches of Therapsids to survive the end-of-Permian mass extinction. The other branch were the Cynodonts ("dog teeth"), the direct ancestors of mammals. Owen also helped define the lungish (Dipnoi), an order of the sarcoptyerians, or lobe-fin fish, some of whom were ancestors of tetrapods. His memoir on the African lungfish, which he named Protopterus, laid the foundations for the recognition of the Dipnoi by Johannes Müller.

In 1854 Owen became superintendant of natural history collections at the British Museum, a post he held until 1881when the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London was opened, which he had helped establish. Among many pubications, Owen's three volume Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Vertebrates (1866–1868) was the most comprehensive treatment since Cuvier's Leçons d'anatomie comparée.

Also notable was his 1863 monograph on the famous Jurassic fossil Archaeopteryx,

a reptilian toothed bird found in Bavaria which, in January 1863, Owen

bought for the British Museum. While Owen described it unequivocally as

a bird, it also fulfilled Darwin's prediction that a proto-bird with

unfused wing fingers would be found,

Owen, Darwin, and Huxley

After Darwin's return from the Beagle

voyage, on October 29, 1836 he was introduced by Charles Lyell to Owen,

who agreed to identify fossil bones collected in South America. Owen's

subsequent findings on Toxodon, Glyptodon (1839), a giant armadillo, and the giant ground sloth Mylodon

(1842), dating from the glacial era of the Pleistocene, showed that

they were large varieties of rodents and sloths. This indicated they

were related to current species in South America, rather than being

ancestors of similarly sized creatures in Africa, as Darwin had

originally thought. This was one of the many influences that led Darwin

later to formulate his own ideas on the concept of natural selection.

Owen

eventually, however, became an antagonist of both Darwin and his chief

supporter, Thomas Henry Huxley. In his role as President-elect of

the Royal Association, Owen presented his own authoritative anatomical

studies of primate brains, claiming that the human brain had structures

that apes brains did not, and that therefore humans were a separate

sub-class. Owen's main argument was that humans have much larger brains

for their body size than other mammals including the great apes.

This

initiated a long-standing feud between Owen vs. Darwin and Huxley.

Darwin wrote that "I cannot swallow Man [being that] distinct from a

Chimpanzee". Thomas Henry Huxley used his March 1858 Royal Institution

lecture to deny Owen's claim, and affirmed that in terms of anatomy,

gorillas are as close to humans as they are to baboons. He believed

that the "mental and moral faculties are essentially... the same kind

in animals and ourselves".

In April 1860 Owen published an anonymous review of On the Origin of Species in the Edinburgh Review,

where he criticized what he saw as Darwin's caricature of his own

axiom of "the continuous operation of the ordained becoming of living

things". Afterwards, Owen's views were criticized repeatedly by

Huxley and, less vocally, by

Darwin.

References:

Owen, R. 1849-1884. History of British Fossil Reptiles (4 vols.) London. British Museum.

Owen, R. 1860. On some reptilian fossils from South Africa. Quaternary Journal of the Geological Association of South Africa 67:1-110.

Owen, R. 1866-1868. Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Vertebrates. London, British Museum.

Owen, R. 1876. Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa. London, British Museum.

.

Copyright © 1996-2020 Rust Family Foundation (All Rights Reserved).